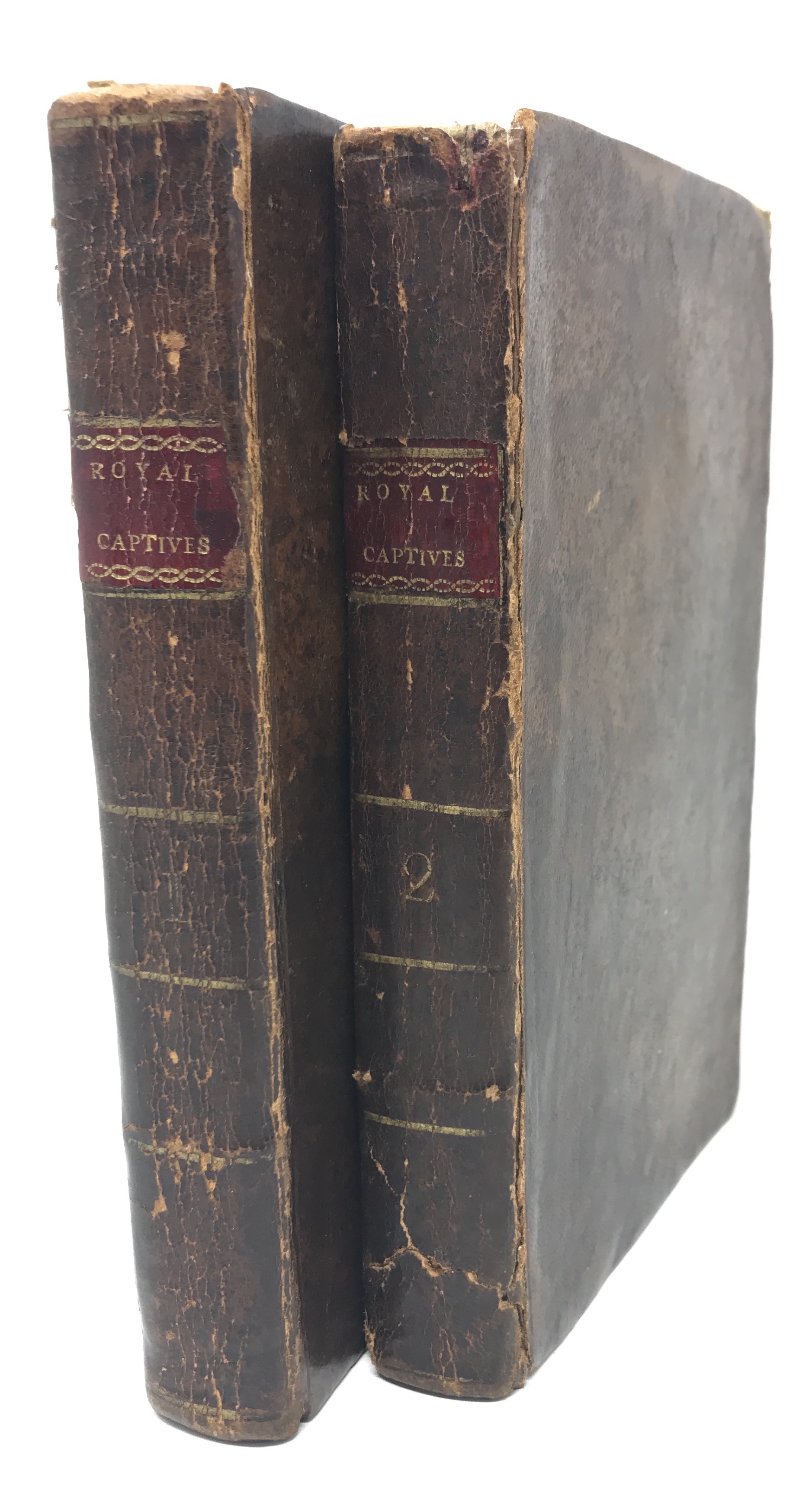

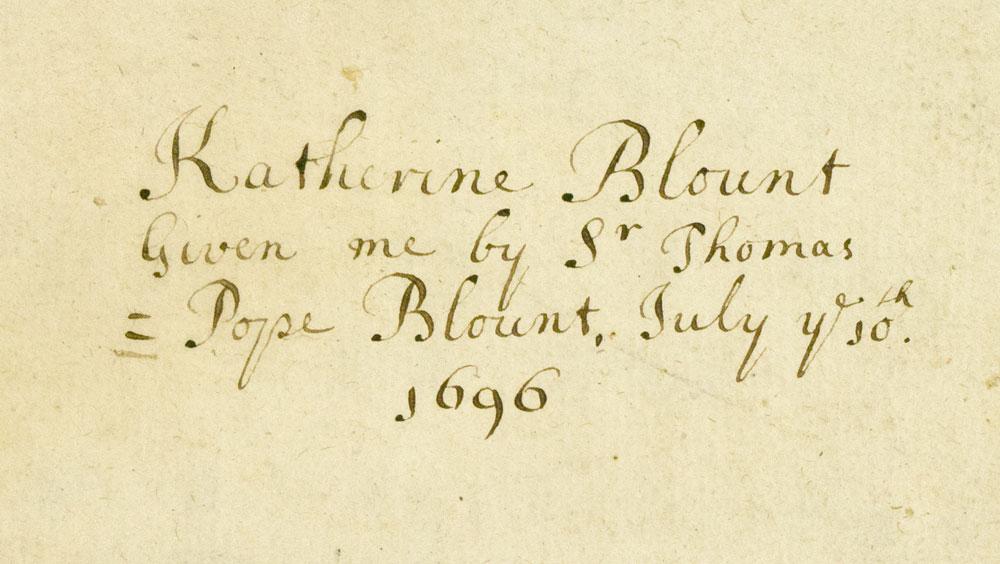

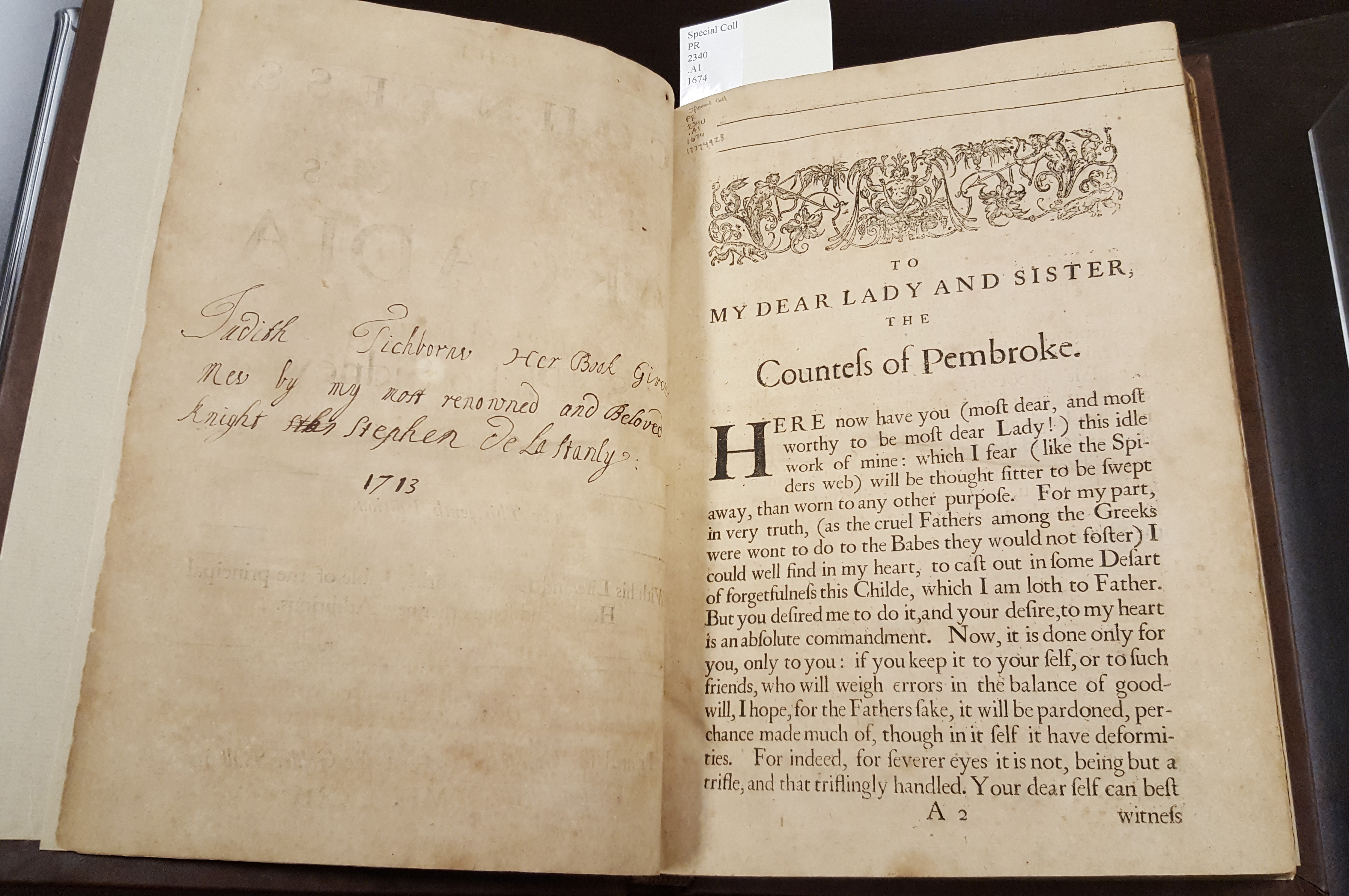

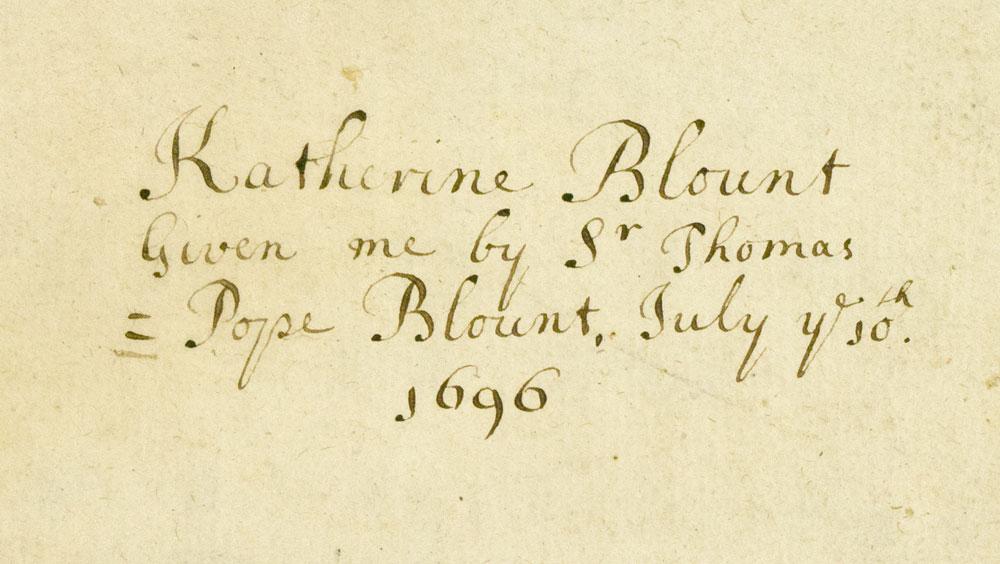

One of the aims of Early Modern Female Book Ownership is to document women owners in the hope of discerning patterns of ownership, whether broader or localized to an individual. In Katherine Blount’s case, I had drafted a post in spring 2019 about a 1656 edition of Edward Reynolds’ A Treatise of the Passions and Faculties of the Soul of Man once in her possession and offered for sale by Blackwell’s Rare Books. She inscribed a front endpaper of the book “Katherine Blount Given me by Sr Thomas=Pope Blount, July ye 10th. 1696.”

To my frustration, I could find little information about Blount, apart from the fact that she was the wife of the 2nd Baronet, Sir Thomas Pope Blount (1670–1731), who married a Katherine Butler in 1695 and therefore must have given Reynolds’ book to her shortly after their marriage. An absence of information is an all-too-common problem in researching the lives of women, both in the early modern period and in more recent times. Many are unknown to the historical records except insofar as they are related to husbands, fathers, and other men.

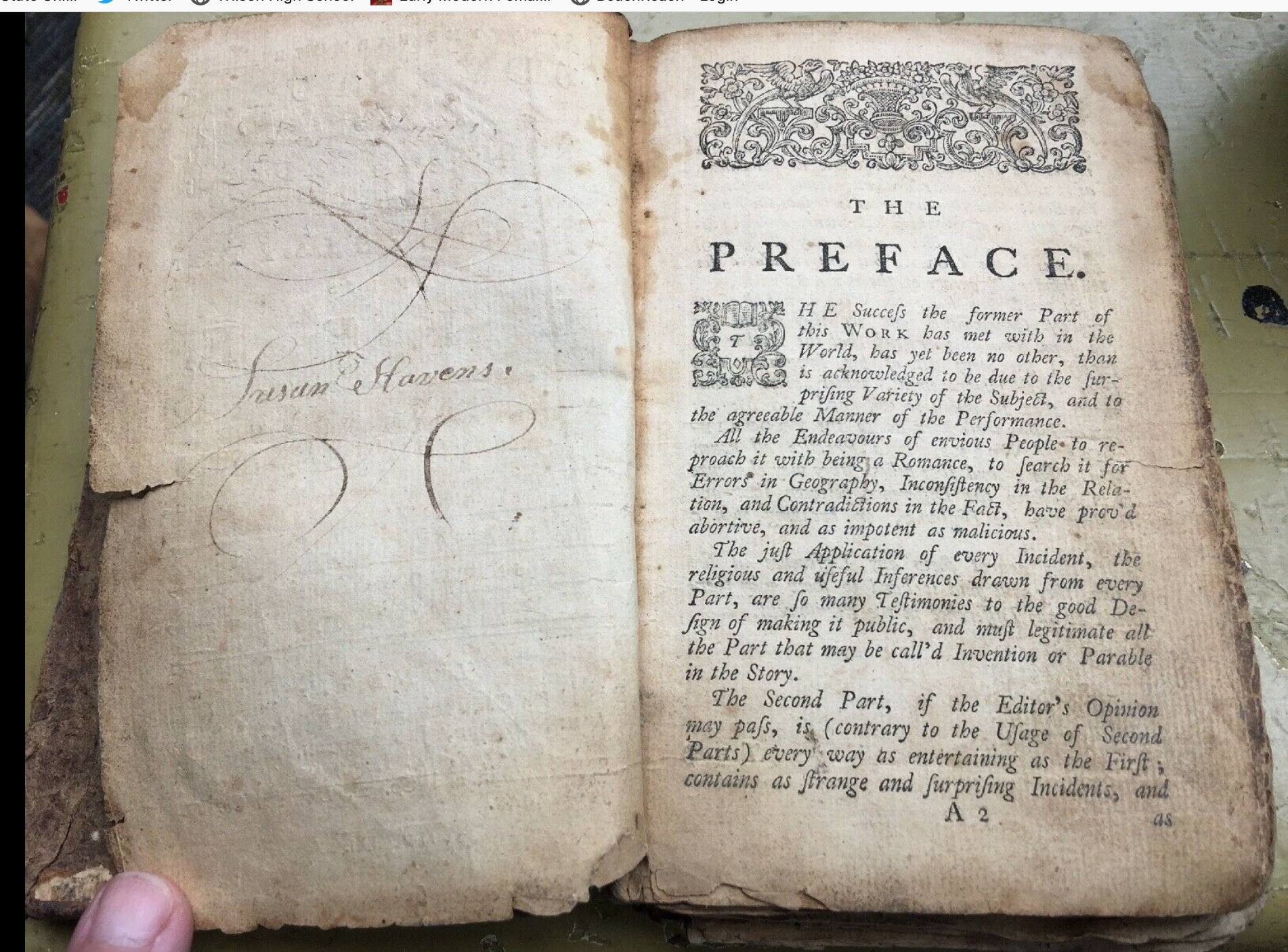

A few months after I drafted my post about Blount, Jarndyce Antiquarian Booksellers offered for sale “an early Ben Jonson folio with contemporary female provenance.” Although the book was sold thereafter and now resides at the Beinecke Library under shelf-mark 2020 +1, Jarndyce was kind enough to allow me to share images of it on this website. It wasn’t until recently that I realized that the previous owner was none other than Katherine Blount.

The hoped-for patterns have emerged. To begin with, we can now link two books recently offered for sale to the same owner, somewhat of a rarity given that we are at the mercy of serendipity when it comes to booksellers’ wares. We can also guess that Blount may have regularly dated new acquisitions to her library and described her sources. The Reynolds book was a gift from her husband, but the 1692 edition of Jonson’s works appears to have been her own purchase, one for which she paid 18 shillings.

The best source of information about Blount’s life I have been able to find so far is an obscure text called A History of Tyttenhanger, written by Lady Jane Van Koughnet of Tyttenhanger House and published in 1895 [1]. Blount was the daughter of James Butler and Grace Caldecott of Amberley Castle, an edifice which is still standing today. She was born in 1676 and became the mistress of Tyttenhanger when she was nineteen, though she and her husband resided primarily at Twickenham. Just as Paul Morgan suggests that Frances Wolfreston was a “stronger character” than her husband, who was described as “meeke and virtuous” in his funeral epitaph, Van Koughnet makes clear that Katherine Blount was worth more notice than Thomas Pope Blount.

Sir Thomas was of a kind disposition, and greatly beloved . . . but there is nothing of his left that points to any talent or taste in particular. His wife, on the contrary, was a brilliant woman, full of cleverness and highly cultivated, fond of poetry, a lover of all that was refined and artistic, interesting herself in the passing world of her day, and gifted with a mind full of energy. Sir Godfrey Kneller’s portrait of her is handsome and determined-looking. She was a friend of Alexander Pope, with whom she corresponded. (65)

Van Koughnet goes on to describe Blount’s “large collection of all sorts of curiosities,” the remnants of which survived at Tyttenhanger at the time of writing. Blount owned, among other objets d’art, a “Chinese cabinet containing a collection of coins,” “Chinese idols, [a] boxwood Romululs and Remus with the wolf, . . . engravings, [and an] ivory crucifix.” Perhaps the most interesting of Blount’s surviving treasures is a “sheath with the ornamental arrows which she wore at a fancy ball, where she went dressed to represent Diana” (66–67).

Unfortunately, Van Koughnet does not say much about Blount’s book collection. Van Koughnet’s remaining pages about Blount mainly consist of letters that Blount received from her eldest surviving son Harry and his tutor. In spite of Blount’s “great pains with the education of her children,” Harry Pope Blount had difficulty managing money and appealed constantly to his mother, after she was widowed in 1731, to rescue him from his debts (68). He did briefly succeed her after she died on March 2nd, 1753, but the Tyttenhanger estate ultimately fell to his sister Catherine Blount Freman and to her daughter Catherine Freman Yorke in 1763. Upon her death, Katherine Blount left to her son “her books, prints, coins, medals, rarities, and curiosities” (91).

Katherine has been at least nominally recognized for her book collecting. Her name is listed in William Carew Hazlitt’s bibliography A Roll of Honour: A Calendar of the Names of over 17,000 Men and Women Who Throughout the British Isles and in Our Early Colonies Have Collected MSS and Printed Books from the XIVth to the XIXth Century, along with a Juliana Blount, relation unknown.

Blount also appears twice in a 1905 record of London book auctions as the recipient of a presentation copy of a third edition of Sir Thomas Pope Blount’s essays [2]. This Blount would have been her father-in-law, the 1st Baronet, who died the same year that the book was published.

I have since been able to link an additional seven books to her library:

Bacon, Sir Francis. The Essays or Counsels, Civil & Moral (London: Printed by T.N., [1673]) Inscribed “Katherine Blount, 1697.” Whereabouts unknown. Cf. Walter, Jerrold. The Autolycus of the Bookstalls (London: J.M. Dent, 1902), p. 189–90.

The Banquet of Xenophon (London: Printed for John Barnes, 1710) Inscribed “Kath: Blount. Given me by ye Dutchess of Marlborough. 1710.” The National Trust, shelf-mark WIM.

Glanvill, Joseph. Lux Orientalis, or, An Enquiry into the Opinion of the Eastern Sages, Concerning the Praeexistence of Souls (London, 1662) Inscribed by Sir Thomas Pope Blount and Katherine Blount; Katherine’s inscription is dated 1697. Whereabouts unknown. Cf. Catalogue of a Further Choice Portion of the Valuable Library of a Well-Known Collector (Sotheby & Wilkinson, [1858]), p. 33.

Kennett, Basil. Romae Antiquae Notitia, or, The Antiquities of Rome (London: Printed for R. Knaplock, 1721) Inscribed by Blount “Left by my Dear Brother the Revd Mr John Pope Blount (who decas’d Apr. 8. 1734) to the Library at Tittenhanger.” The National Trust, shelf-mark WIM.

Pepys, Samuel. Memoirs Relating to the State of the Royal Navy (London: Printed for B. Griffin, 1690) Inscribed “Katherine Blount price 6s., 1700/1.” Whereabouts unknown. Cf. Book-Prices Current, volume 27 (1913), p. 499.

Somers, John. A Discourse Concerning Generosity (London: Printed for J.A., 1695) Inscribed “Kath: Blount” and dated “1705.” British Library, shelf-mark 4403.bb.30. Cf. Rudolph, Judith. Common Law and Enlightenment in England, 1689-1750 (Boydell Press, 2013), p. 193.

Willughby, Francis. The Ornithology . . . In Three Books (London: Printed by Andrew Clarke, 1678) Inscribed “Katherine Blount Given me by Mrs. Pope 1730.” The National Trust, shelf-mark WIM.

These seven books demonstrate the breadth of Blount’s reading interests and also confirm that she did indeed systematically date new additions to her library as the inscriptions in her Reynolds and Jonson attest. The acquisition dates of the books described in this essay span a thirty-eight year period from 1696 to 1734. Katherine lived an additional nineteen years after 1734, and it will be interesting to see if any of her books emerge which are dated after this year. Her son Harry sent her a letter in October 1738 thanking her for “ye gift of Theophilus etc: wch I have once read, & design to read it often carefully Over,” so it seems clear that books continued to play an important role in her life and that of her family well into the 1730s, and probably beyond (79). It would be interesting, too, to delve into how the National Trust came to hold three of her books and whether there are any more besides. Another avenue worth taking would be Blount’s relationships with the women and men who gave her books, particularly Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough and “Mrs. Pope.”

Source: Edward Reynolds title offered for sale by Blackwell’s Rare Books. The Jonson was offered for sale in October 2019 and has since been acquired by the Beinecke Library at Yale. Images used with permission.

Additional Reading

[1] Van Koughnet, Lady Jane. A History of Tyttenhanger (London: Marcus Ward & Co., [1895])

[2] Karslake, Frank. Book-Auction Records: A Priced and Annotated Record of London Book Auctions: Vol. II: October 1, 1904–September 30, 1905 (London: Karslake & Co, 1905), p. 202, 348.