Michael Durrant (IES, University of London)

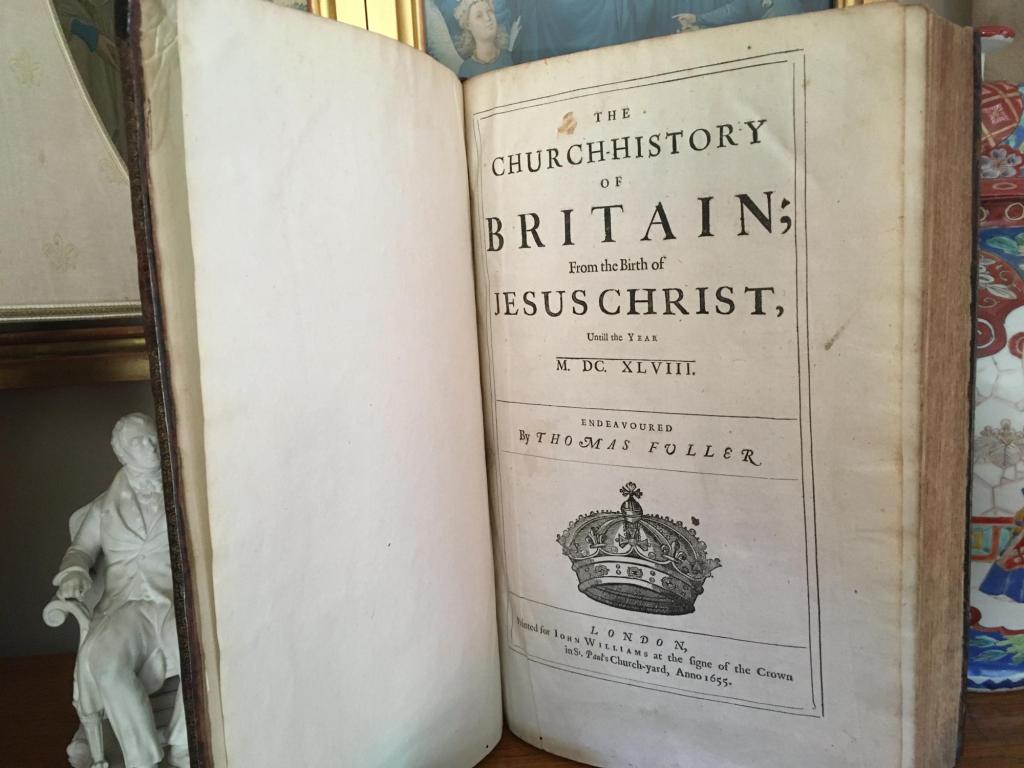

One of Senate House Library’s copies of Charles I’s ghost-written memoir, Eikon Basilike. The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in his Solitudes and Sufferings, which was printed by “W[illiam]. D[ugard].” for Francis Eglesfield in 1649, contains a manuscript inscription on the verso side of its front endpaper. This undated inscription looks to the future of the book’s ownership, but it also imagines possible futures for that book’s female owner:

this Book at my Decease to Mr Morgan Mrs Morgans only son by her Husband Mr Thomas Morgan Drapier at Bromsg[rove] in ye county of Worcester now a Dowager till God is pleased to send Her a second mate.

Presumably, the ‘Mrs Morgan’ identified here is also the inscriber. She stipulates that upon her death, her copy of the Eikon was to pass into the possession of her “only son,” securing not only that book’s survival but also helping to reinforce maternal bonds. Mrs Morgan’s husband, Thomas, was already dead, which left her as a dowager, but Mrs Morgan clearly did not understand her dowagerhood as a fixed or finalized state, but rather one that might be reformed by remarriage.

If Mrs Morgan recognized that there was life after death—after the death of her husband, that is—she must also have identified the book as a powerfully symbolic object into which those imaginings could be etched. And not just any book but Eikon Basilike, a “Sacred” text that royalist writers celebrated as a “Living Memoriall,” as a kind of holy relic, which, in the wake of the regicide, functioned as a textual vessel and substitute for Charles I’s decapitated, corporeal form.[1] The Eikon gave posthumous life to the dead king, but as the inscription above indicates, it also gave Mrs Morgan the opportunity to think about what might come next: to think about where her book might go when she, like Charles I, passed on from one world to the next and to think, too, about the possibility of a new life before that, a new life as the wife of a God-sent “second mate.”

None of this is unusual, especially where the Eikon is concerned since this book has particularly rich historical associations with female ownership. Not only did early modern mothers pass copies onto their sons, but also onto daughters, granddaughters, and beyond, either by way of inheritance or in the form of a gift.[2] Copies of the Eikon also moved between families and therefore into the hands of “different female owners.”[3] As such, a single copy of Eikon Basilike might bear the traces of multiple female owners who were at a genealogical, geographical, and temporal distance from one another, but whose inscriptions form a discreet archive of copy-specific female book ownership bridging considerable distances of time and space.

If we turn now to another copy of the Eikon held at Senate House Library, we can find confirmation of this. Printed by Roger Daniel in 1649, this Eikon Basilike features the ownership mark of one “Frances Vavasour,” accompanied by the familiar phrase “Her Booke” and the date, “1669.” Vavasour’s name and her claim to ownership has been signed on the verso side of the first leaf, directly facing the main title page, which has been ruled in red by hand. Indeed, the whole book is ruled in red, and other user-generated additions include manipulations of William Marshall’s (fl. 1617-1649) famous engraving, which depicts Charles I kneeling at a basilica and which in this particular copy has been lovingly painted by hand.

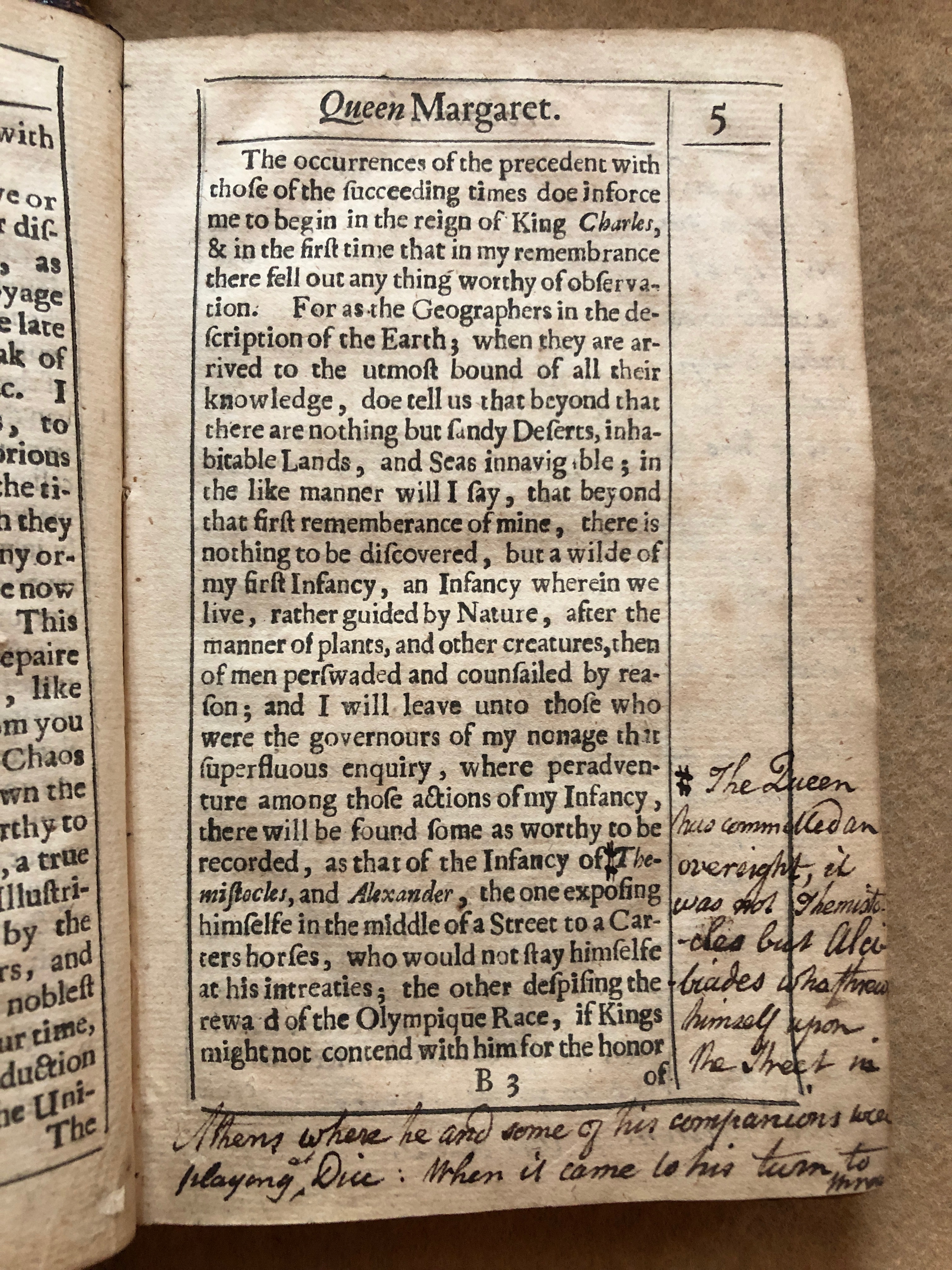

Frances Vavasour is not the only woman present in this copy of the Eikon. One “Mary Wray” has signed her name at the top-left corner of the title page, and two other names circle that paratextual surface: “P. Dalton” and “E. Carnarvon.” None of these signatures are dated, and the partial nature of the evidence is only exacerbated by the fact that a possible fourth name has been cut away at the top of the page, leaving a gap between Wray and Dalton. Yet even in the face of excised evidence, the close proximity of the names “Frances Vavasour” and “Mary Wray” in the same book does help us to identify who these figures might have been and how they were related to each other.

A Frances Vavasour (1654–1731) of Copmanthorpe, Yorkshire, married Sir Thomas Norcliffe (1641–1684) of Langdon, Yorkshire, in 1671, becoming Lady Frances Norcliffe.[4] They had two sons: Fairfax Norcliffe (1674–1721) and Richard Norcliffe (1676–1697). Fairfax’s daughter (and Lady Frances’s granddaughter), Frances Norcliffe, married one John Wray (1689–1752), and their daughter (and Lady Frances’s great-granddaughter) was called Mary Wray (c. 1745–1807).[5] So, one scenario is that this copy of the Eikon passed from great-grandmother to great-granddaughter (perhaps by way of Frances’s daughter, who also inherited her mother’s first name). Additionally, since the evidence seems to point to Frances Vavasour being Lady Frances Norcliffe, she must have signed her copy of the Eikon not too long before her first marriage to Thomas—following his death in 1684, Frances married her “second mate,” to quote Mrs Morgan again, this time an Aleppo merchant—and right around the time that Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680) painted her bust-length portrait.[6]

Given the historical remits of this blog, this should mark the logical limits of where the story of this book’s ownership should end; however, over the course of the following century, Frances’s “Booke” fell into the hands of another female owner. On the recto side of the leaf bearing Vavasour’s ownership inscription, and just above an engraving featuring the Stuart coat of arms, we find the name “E. M. A. Austen,” which is dated “1909.” Towards the bottom of the same page, there’s a further note related to the Austens, this time memorializing the fact that the book was passed down from one generation to the next as a birthday gift: “Elizabeth J. Hampden Austen with loving good wishes for her 21st birthday from aunt Edith”—who might be the “E. M. A. Austen” who signed and dated the book in 1909—“and aunt Lily. December 3rd 1942.”

Fortuitously, Elizabeth J. Hampden Austen’s life is fairly well documented. According to her obituary,[7] Elizabeth J. Hampden Austen (or rather Sister Martin Dominic Austen) was born in Oxfordshire in 1921, the daughter of an Anglican clergyman. She joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service during the Second World War, and after the war she converted to the Roman Catholic faith. Sister Martin subsequently joined the Dominican Sisters of Bethany in France, and for the remainder of her life and career, she moved between Europe and the US, living with religious communities in Italy and Switzerland and helping to form communities in Massachusetts and elsewhere in the US. Sister Martin was also well known for her pastoral work with female prisoners in a variety of penitentiaries in Maine, Connecticut, and New York. She died in Portland, Maine, in February 2018.

By now we are really at quite some distance from the early modern, but as Whitney Trettien has argued, “the history of reading,” and of the period’s “used books,” “is also a history of mediating the material world, a narrative that, by its nature, pleats the past, present, and future.”[8] The two copies of Eikon Basilike discussed here perform this temporal pleating in all kinds of ways, and both copies have clearly played an important role in the life cycles of early/modern women. Mrs Morgan’s inscription looks to the past in that it commemorates “her Husband Mr Thomas Morgan Drapier at Bromsg[rove] in ye county of Worcester”; it meets us in the “now” of her writing, when Mrs Morgan found herself “a Dowager,” although she’s looking to the future, too, the future of her “Book,” her “only son,” and her own marital status. Frances Vavasour’s inscription firmly places us in 1669, but knowing what comes next—her marriage to Sir Thomas Norcliffe and her sitting for Lely’s portrait were just around the corner—conjures a sense of the transitional, even liminal contexts in which her claim to book ownership was made. In the inscription from 1942, Eikon Basilike again becomes a material space in which to mark out another kind of turning point, this time a woman’s twenty-first birthday, and it’s one that’s set against a global war, a future confessional turn, as well as a much deeper history of female ownership, which might well take us back to “E. M. A. Austen” in 1909 and almost certainly to Mary Wray in the eighteenth century and Frances Vavasour in the 1600s.

When aunts Edith and Lily gave Eikon Basilike to Elizabeth as a birthday gift in 1942, did the book’s long history of female ownership play a special part in their estimations of that gift’s symbolic significance? What did Elizabeth make of her gift and of Frances and Mary’s presence within it? Did she—and might we—treat their temporally-distant inscriptions as “marginal beside-text[s],” to quote Trettien again, each framing the “future readers’ encounters with the other”?[9] I don’t have the answers, but both copies do invite us to think, like Mrs Morgan, about the future—the future shapes, say, of our histories of early modern female book ownership, particularly as they pertain to where those histories might begin and, given the present discussion, where they might end.

Source: copies held at Senate House Library, 1) shelf mark ([Rare] (VIII) [Charles I] 5); and 2) shelf mark ([Rare] (VII) Cc [Charles I] 7). Photos by Michael Durrant, reproduced with permission.

[1] Anon, The Princely Pellican. Royall Resolves Presented in Sundry Choice Observations, Extracted from His Majesties Divine Meditations (London: [s.n.] 1649), p. 1.

[2] https://earlymodernfemalebookownership.wordpress.com/2022/07/28/charles-i-eikon-basilike-1649-2/

[3] https://earlymodernfemalebookownership.wordpress.com/2021/04/19/charles-i-eikon-basilike-1649/

[4] Carrying on the Yorkshire theme, this copy of the Eikon eventually passed into the ownership of Sir Mark Masterman-Sykes (1771-1823), a landowner, politician, and well-known bibliophile based in Sledmere near Leeds. His vast library was sold off in 1824, and so this book, which features Masterman-Sykes’s bookplate affixed to front board, must have been dispersed as part of the 3700 lots that made up that auction (and which fetched nearly £18,000). See Alan Bell, “Sykes, Mark Masterman, third baronet (1771-1823), book collector,” ODNB (2004), https://0-www-oxforddnb-com.catalogue.libraries.london.ac.uk/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-26869.

[5] I have drawn this biographical outline from the description provided in John Burke, A Genealogical and Heraldic History of the Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 2 (London: Henry Colburn, 1835), p. 631.

[6] For Lady Norcliffe’s portrait, see https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5521215

[7] https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/mainetoday-pressherald/name/martin-austen-obituary?id=12153877

[8] Whitney Trettien, “Media, Materiality, and Time in the History of Reading: The Case of the Little Gidding Harmonies,” PMLA 133:5 (2018), pp. 1135-51 (p. 1138).

[9] Ibid., p. 1149.

![140- 712q [230]](https://earlymodernfemalebookownership.files.wordpress.com/2020/08/folger-140-712q-last-page.jpg)