By Molly G. Yarn

The Rasmussen Hines Collection holds a copy of the third edition of Sir John Suckling’s works, Fragmenta Aurea (1658), with a complex and interesting #herbook provenance.

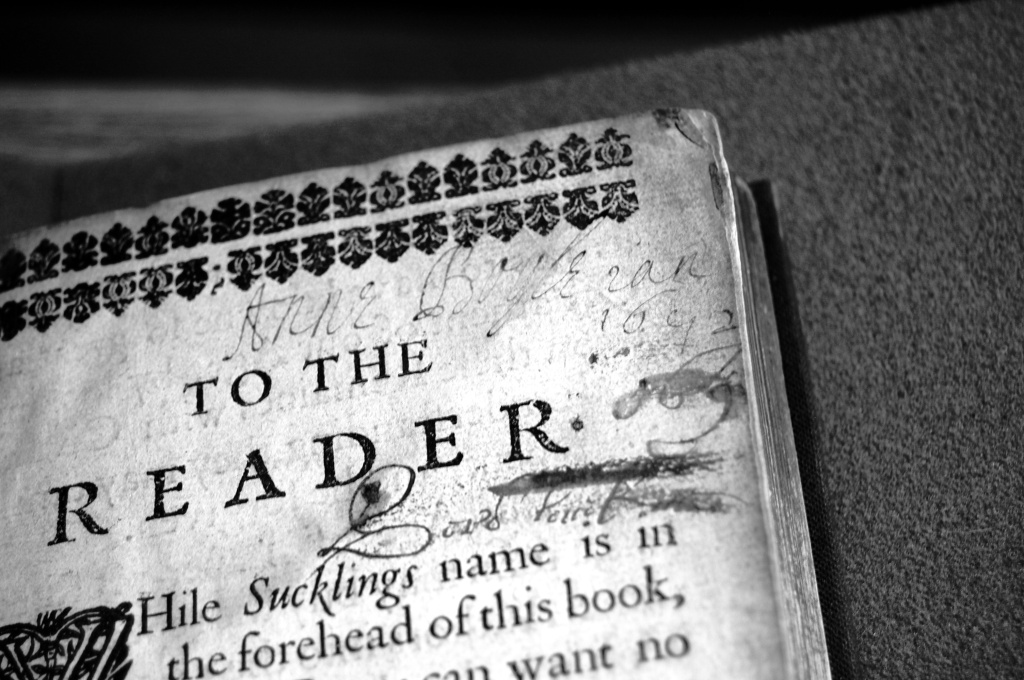

The first dated inscription in this copy is that of “Anne Boyle,” 1673. Although not a terribly unusual name, several other inscriptions in the volume, including the names “Coote” and a cut-off “Blesinton,” allow us to identify Anne confidently as Lady Anne Coote Boyle (1658–1725), Viscountess Blessington. Anne was the daughter of Charles Coote, the second Earl of Mountrath (1628–1672) and Alyce Meredith. Anne’s grandfather Charles, first Earl of Mountrath (a brutal soldier and rapacious acquirer of Irish land, and by all accounts a ruthless oppressor of Irish Catholics), led Parliamentary forces in Ireland and served in the protectorate parliaments but managed, with his ally Roger Boyle (Lord Broghill and the future Earl of Orrery), to switch sides, offering his support to Charles II prior to the Restoration and becoming Earl of Mountrath for his efforts. Coote’s son Charles, the second Earl and Anne’s father, outlived his father by only ten years and seems not to have been a significant political player; however, the Cootes were major Protestant landowners with several large ironworks and strongly positioned for success after the Stuarts returned.[1] In 1672, the same year as her father’s death, Anne Coote married Murrough Boyle (c. 1645–1718), a member of the powerful Boyle clan and cousin to Mountrath’s ally Roger Boyle, Earl of Orrery. The following year, Murrough Boyle became the first Viscount Blessington (originally spelled “Blesinton”). In addition to Anne’s 1673 signature, this ornate signature several pages later, which appears to read “A Blesint—,” is likely also hers.

Murrough Boyle, Viscount Blessington, was a man with literary ambitions – he was the author of a tragic play entitled The Lost Princess, which a critic described as “truly contemptible” (Doyle, “Boyle, Murrough”). As a member of the Boyle family, he also had numerous literary connections that make this copy of Fragmenta Aurea’s provenance particularly interesting. Roger Boyle, first Earl of Orrery, was himself an accomplished author and friend to many writers, including John Suckling himself. One of Suckling’s poems in Fragmenta Aurea, “Ballade upon a Wedding,” may have been written to commemorate Roger Boyle’s marriage to Margaret Howard. Orrery and his siblings – Richard Boyle, second Earl of Cork, and his wife, Elizabeth Clifford, Katherine Boyle Jones, Lady Ranelagh, Mary Boyle Rich, Countess of Warwick, Robert Boyle, the chemist, and Francis Boyle, first Viscount Shannon, and his wife Elizabeth Killigrew, sister of writers William and Thomas Killigrew – were all, in their own rights, major figures in the English literary and intellectual circles of the mid to late seventeenth century.[2]

In her discussion of the Boyle women’s life writing, Ann-Maria Walsh emphasizes the significance of dynastic marriages to the Protestant “New English” families of landowners in Ireland, and Murrough and Anne’s marriage sits within a complex and shifting network of alliances. Anne’s grandfather, Charles Coote, was allied with Roger Boyle, the first Earl of Orrery; they served together as two of the three lord justices of Ireland in 1660. In this context, a marriage between the two families makes sense. Murrough Boyle, however, came with his own set of baggage. He was the son of Michael Boyle, archbishop of Dublin and the lord chancellor of Ireland. Although Michael Boyle and his father had benefited from the influence of their more powerful cousins, particularly the earls of Cork, Michael Boyle married the Hon. Mary O’Brien in the 1640s. Mary was the sister of Murrough O’Brien, the first Earl of Inchiquin and a long-time enemy of Orrery. Michael Boyle aligned himself with the O’Briens, even serving as Inchiquin’s emissary during delicate negotiations. The Inchiquin-Orrery feud is too complex to detail here; however, the two men decided to make peace during the late 1660s, cementing their friendship with a marriage between Orrery’s daughter Margaret and Inchiquin’s son William in 1665. Orrery’s son Henry would also marry Inchiquin’s daughter Mary in 1679. The 1672 marriage between Anne Coote, daughter of a close Orrery ally, and Murrough Boyle, cousin of Orrery and nephew of Inchiquin, whose branch of the Boyles had recently been reconciled with the Cork/Orrery branch, fits into this pattern of dynastic and political alliances.[3] The personal connection between Orrery and Suckling, particularly the link between Orrery’s own wedding and one of the volume’s poems, make this book a remarkably evocative item for Anne to have acquired, or at least inscribed, the year of her own marriage into the Boyle family.

The Coote connection links Anne to another interesting woman-owned book, which has been described by Kate Lilley. Anne Tighe Coote was the wife of Anne Coote Boyle’s second cousin Thomas and the owner of a 1669 edition of Katharine Phillips’ Poems. Her copy, now held at the National Art Library at the V&A, includes a transcription of a poem entitled “The Teares of the Consort for Mr Tighe Writt by My Lord Blessington 1679,” signed by “Ann: Tighe: August ye 26th 1680.” “Mr Tighe” was Anne Tighe’s first husband, William, who died in 1679; “My Lord Blessington” was, of course, Murrough Boyle, Anne Coote Boyle’s husband. Anne Tighe owned the book before her marriage into the Coote-Boyle family in 1680 (the monogram on the binding, “ANTIGHE,” indicates that it was likely bound, or at least stamped, during her marriage to William Tighe, 1675–1679), but the choice to inscribe it with Murrough Boyle’s poem seems deliberate, a nod to her future husband’s family connections and, likely, an indication that Anne Tighe developed a personal relationship with Anne and Murrough Boyle. Katharine Phillips was closely involved with the Boyle circles – she dedicated various poems to Elizabeth Boyle, Countess of Cork, and her daughters, and the Earl of Orrery wrote one of the volume’s commendatory poems. Clearly, Anne Tighe was aware of the Boyle family’s patronage of Phillips, and this inscription reflects, in Lilley’s words, “a complex web of associations” similar, and related to, the one found in the Coote-Boyle copy of Suckling (121).

Anne Boyle may have only kept Fragmenta Aurea for about a year of her married life. By 1673, some time after she and Murrough became Viscountess and Viscount Blessington (as indicated by the “ABlesint” signature) she had passed it along to a new owner, at least temporarily – “Coote” is written on the dedication page and, although it has been scratched out, “Charles Coote His Booke 1673” appears opposite the title page of The Last Remains of John Suckling.

Taking the date into account, this Charles Coote was most likely Anne’s brother, the third Earl of Mountrath. Like his brother-in-law Blessington, Coote supported Hugh Capel and experienced a brief rise in his political fortunes during the mid 1690s, then a fall into irrelevance.

The signature below Charles’s throws an additional curve ball: “Elizabeth Adshead her booke 169-.” Unfortunately, the binding hides the final digit of Elizabeth’s date, but, if accurate, this suggests that Charles Coote had passed the book along by 1699 at the latest. Based on this, and the loss at the edges, the copy was trimmed and bound sometime after c. 1700.

The matching lower-case “th” in “Elizabeth,” “tho,” and “that” suggests that Elizabeth herself wrote something like “the man is bleest that” below her signature. I have been unable to identify Elizabeth Adshead. A large Adshead family is associated with Cheshire, but I see no links between them and the Coote-Boyles. The line below offers another clue:

It appears to read “alizabeth kinder her,” but there is certainly room for interpretation in that transcription. The similarity between the “d” in Adshead and in “kinder” inclines me to think that Elizabeth Adshead wrote all three lines. If it is a name, perhaps it is her maiden name? It could also be a continuation of the quotation (if such it is) on the line above: “______ hath hinder her,” maybe?

If Charles Coote was the book’s owner until the 1690s, his family’s fortunes could explain how the book ended up with a new owner. As a Protestant supporter of William and Mary, Charles Coote’s estates were forfeited during the Jacobite-Williamite War (1688–1691), although they were restored and enlarged after William’s victory. Many large houses belonging to Williamites were looted. The Coote family supposedly experienced “considerable deprivation” during the War, with Coote’s wife, Isabella, dying “out of grief, pawning her last ring” (Doyle, “Coote, Charles”). The book, along with many of his other belongings, could have left his possession during that period. One more inscription in the book, however, may hint at another owner before 1689-1691:

Although partially scratched out, image manipulation reveals more details:

The date under “1672” appears to be “1679,” although it could also be “169_,” with the last digit cut off during rebinding. I am inclined toward “1679,” however, with the “7” set slightly above the “9” and connected to the “6.” Although it’s difficult to be sure, the handwriting appears to slightly resemble Anne’s above (see the similarity of the “6”); if this is the case, Charles Coote may have returned the book to his sister, who added the additional date and crossed out Charles’s inscription on the later page to reassert her ownership. In that case, a different narrative would be required to explain why the book passed out of the Coote-Boyle family’s hands. Murrough’s father, Michael Boyle, built an enormous mansion at Blessington, in County Wicklow, around the time of Anne and Murrough’s marriage, which was “plundered” in 1689 (Breffny). Perhaps it ended up in the library there? As Walsh explains, however, the Boyle women were extremely mobile, traveling to family properties across Ireland and England. The Cootes either owned or let a London house in Soho Square, where Murrough is known to have stayed with them (Barnard, 331). Either Anne, Charles, or an unknown person could have left, lost, or given away the book in any number of places around England and Ireland, making the timeline of its ownership quite murky.

Speaking of an unknown person, however, if 1679/169_ does not belong with Anne’s inscription, it may be associated with the partially lost text beneath it. That handwriting, in combination with the forceful erasure, is challenging, but I’m currently inclined to read it as “Lord” and something like “Peiret”; if this rings a bell with anyone, I’d be very happy to hear from you!

Source: Rasmussen Hines Collection. Photos by Molly G. Yarn, reproduced with permission.

Further Reading

Toby Christopher Barnard, Making the Grand Figure: Lives and Possessions in Ireland, 1641-1770 (Yale University Press, 2004).

Brian de Breffny, “The Building of the Mansion at Blessington, 1672,” The GPA Irish Arts Review Yearbook, 1988, 73–77.

T.J. Doyle, “Boyle, Murrough,” Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009 <doi.org/10.3318/dib.000851.v1>

T.J. Doyle, “Coote, Charles,” Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009 <doi.org/10.3318/dib.002019.v1>.

Kate Lilley, “Katherine Philips, ‘Philo-Philippa’ and the Poetics of Association.” Material Cultures of Early Modern Women’s Writing, ed. by Patricia Pender and Rosalind Smith (Palgrave MacMillan, 2014), pp. 118–39.

Jane H. Ohlmeyer, Making Ireland English: The Irish Aristocracy in the Seventeenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

Ana-Maria Walsh, “The Boyle Women and Familial Life Writing.” Women’s Life Writing and Early Modern Ireland, ed. by Julie A. Eckerle and Naomi McAreavey, Women and Gender in the Early Modern World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), pp. 79–98.

[1] For the Coote-Boyle clan’s involvement in 17th century politics, see (among many others) Ohlmeyer.

[2] See individual entries in the ODNB and the Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[3] There are documents related to the negotiation of their marriage and to Murrough Boyle’s financial affairs in the De Vesci papers at the National Library of Ireland [MS 38,748/4; MS 38,831/1-2; MS 38,837].