By Ynys Convents, Ellen Gommers, Sebastiaan Peeters, Emma Ten Doesschate,

and Patricia Stoop (University of Antwerp)

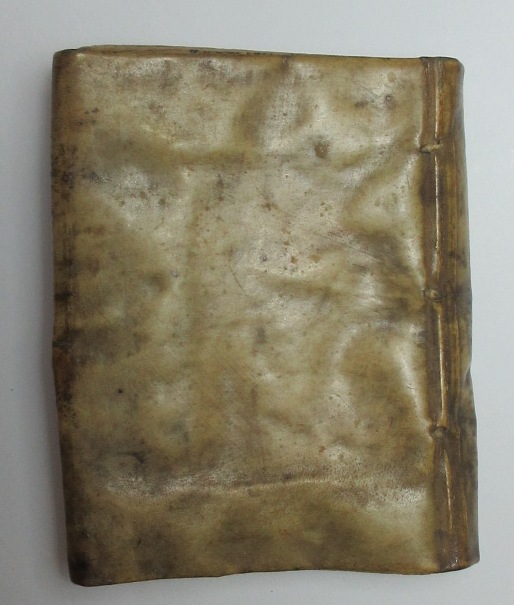

Women’s contribution to the literary culture of the early modern Low Countries is still very much underexposed. Fascinating research done in recent years has not yet reached the general public. Many other sources have not been studied thus far. Therefore, students of Dutch at the University of Antwerp studied seven early printed books from the seventeenth century that are preserved in the library of the Ruusbroec Institute of the University of Antwerp (https://www.uantwerpen.be/en/research-groups/ruusbroec-institute/library/). Each of these religious books can be linked to women in at least two ways. They dealt with women’s exemplary lives, were written or printed by or dedicated to them, and, at a later stage, found their way to female owners. In this blogpost we present the students’ findings.

Theresa of Ávila as a Source of Inspiration

The works of the influential Spanish mystic, saint, and Doctor of the Church Theresa of Ávila (1515–1582) became widespread across Europe soon after her death, partly under the influence of the Counter-Reformation. Her reformed ideas that led to the foundation of the Order of Discalced Carmelites in 1562 also reached the Catholic part of the Netherlands. Several of her texts were translated — sometimes indirectly via French — into Dutch. The Bibliography of the Hand Press Book in Flanders (STCV: Short Title Catalogue Vlaanderen; https://vlaamse-erfgoedbibliotheken.be/en/dossier/short-title-catalogue-flanders-stcv/stcv) lists seventeen different Dutch-language books, some of which were printed multiple times. In addition, several of her texts in Spanish, French, and Latin were also distributed in the Southern Netherlands.

The Bruydegoms vrede-kus oft Bemerckingen vande liefde Godts (Bridegroom’s Peace-Kiss or Reflections on the Love of God), in which Theresa described various sorts of prayer, was printed in 1647 by the widow of the Antwerp printer Jan Cnobbaert (1590–1637). The work was annotated by the Spanish Carmelite Jerónimo Gracián (1545–1614), Theresa’s spiritual mentor. The Discalced Carmelite Antonius of Jesus produced the Dutch translation at St Joseph’s Convent in Antwerp (as he did for many of her other works). He dedicated the translation to Françoise de Bette (1593–1666), who was the abbess of the Benedictine convent in Vorst near Brussels from 1637 until her death.

In 1687 Hieronymus Verdussen V (1650–1717) printed Den catechismus van S.te Theresia (The Catechism of St Theresa) in Antwerp. According to the title page, Petrus Thomas a S. Maria (1611–1686), a Discalced Carmelite from Normandy, gathered the spiritual teachings “uyt de Schriften ende eygen Woorden vande selve Heylige” (“from the writings and own words of the same saint”). He published the result in French in Rouen in 1672. His French version was translated by a person who only left his initials M. AE. S. in the Antwerp edition and therefore cannot be identified.

Additionally, the library of the Ruusbroec Institute keeps a Dutch translation of Theresa’s biography by the Spanish Jesuit Francisco Ribera (1537–1591). The Spanish version (La vida de la madre Teresa de Iesus) was published in Salamanca in 1590. The anonymous Dutch translation, entitled Het leven der H. Moeder Terese van Iesus fundaterse vande barvoetsche carmeliten ende carmeliterssen (The Life of the Holy Mother Theresa of Jesus, Founder of the Discalced Carmelites), was printed in Antwerp thirty years later by Joachim Trognesius (between 1556 and 1559–1624). Whether the translation was made directly from Spanish or, as in the previous example, from French is not clear. It is certain, however, that a French version by the Carmelite Jean de Brétigny (1556–1634) and the Carthusian Guillaume de Chèvre circulated in the Netherlands: the 1607 edition of La vie de la mere Terese de Jesus was published in Antwerp by Gaspar Bellerus (fl. 1606–1617).

The Lives of Spiritual Virgins

Some inspirational women from the Low Countries also helped shape literary and devotional culture. We know a great deal about them because they documented their lives and religious experiences extensively in diaries and correspondences with their confessors. Based on this auto-biographical documentation, their Lives were written. The Jesuit Daniël Huysmans (1643–1704), for example, wrote biographies of Agnes van Heilsbagh (1597–1640) and Joanna van Randenraedt (1610–1684), who were both spiritual daughters — unmarried women who wanted to lead a religious life, often under the spiritual guidance of Jesuits, without joining a convent. Both Agnes and Johanna lived in Roermond in Limburg (nowadays located in the Netherlands) and were involved in education and the promotion of Christian values. Their biographies in Huysmans’s versions were printed in Antwerp shortly after each other. Kort begryp des levens ende der deughden vande weerdighe Joanna van Randenraedt (Short Account of the Life and Virtues of the Honorable Joanna van Randenraedt) was published and printed in 1690 by Augustinus Great (fl. 1685–1691); Leven ende deughden vande weerdighe Agnes van Heilsbagh (Live and Virtues of the Honorable Agnes Heilsbagh) appeared a year later and was printed by Michiel Knobbaert (fl. 1652–1706). Huysmans integrated the letters of both spiritual daughters into his Lives, which allowed the voices of these women to resonate distinctly in his texts.

Finally, the Carmelite tertiary and mystic Maria Petyt (1623–1677) wrote an autobiography and corresponded with her spiritual counsellor Michael a Sancto Augustino (1621–1684). He published Maria’s texts posthumously in Het leven vande weerdighe moeder Maria a S.ta Teresia, (alias) Petyt, Vanden derden Reghel vande Orden der Broederen van Onse L. Vrouwe des berghs Carmeli (The life of the honorable mother Maria a Sancta Teresa, (alias) Petyt, from the Third Rule of the Order of the Brethren of Our Lady of the Mount Carmel), which came out in Ghent in 1683. Michael claims not to have modified any of Maria’s words in his four-volume publication of no fewer than 1,500 pages. He, however, added a short introduction to each chapter.

Books in Women’s Hands

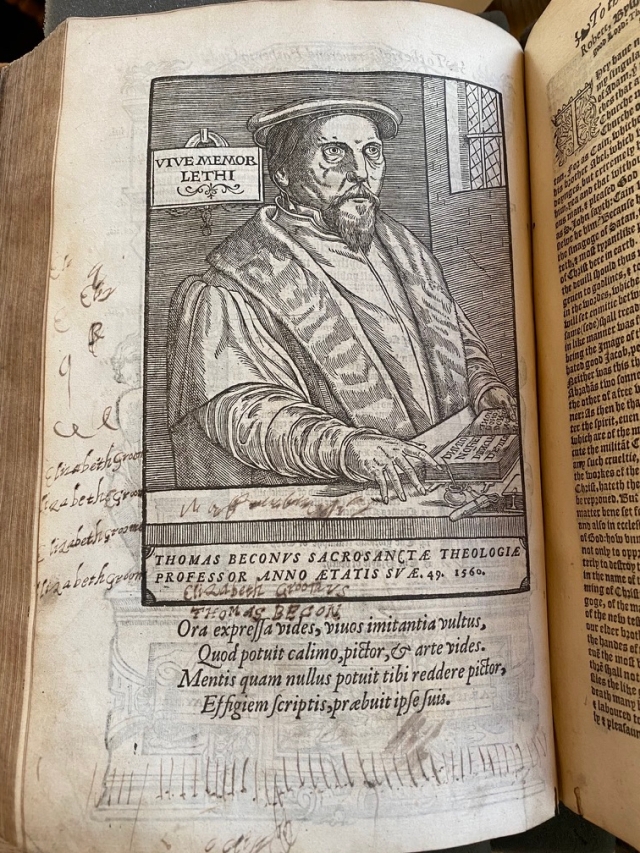

These works by and about women were often destined for a female readership. This is evident from the many ownership inscriptions we discovered. Most of the books ended up in female communities. Theresa of Ávila’s Bruydegoms vrede-kus, for instance, belonged to Catrijn de Roos, who lived “opt groodt begijn hof” (“in the large beguinage”; fly leaf at the front) of an, unfortunately, unspecified town. Some of the books belonged to Alexian sisters (“zwartzusters”). The Life of Agnes van Heilsbagh was owned by her namesake Agnes Vandervloet, who lived in the Alexian community in Antwerp. Het leven der H. Moeder Terese van Iesus was kept in the convent of Alexian sisters in Ypres for no fewer than 175 years. It was donated to the community by Nicolais Reynier in 1624 (Figure 4). There, Sister Catalijn van der Bogaerde owned it. A note at the end of the book further shows that in 1788 it was still in the convent, now being kept by Sister Theresia Verbeke.

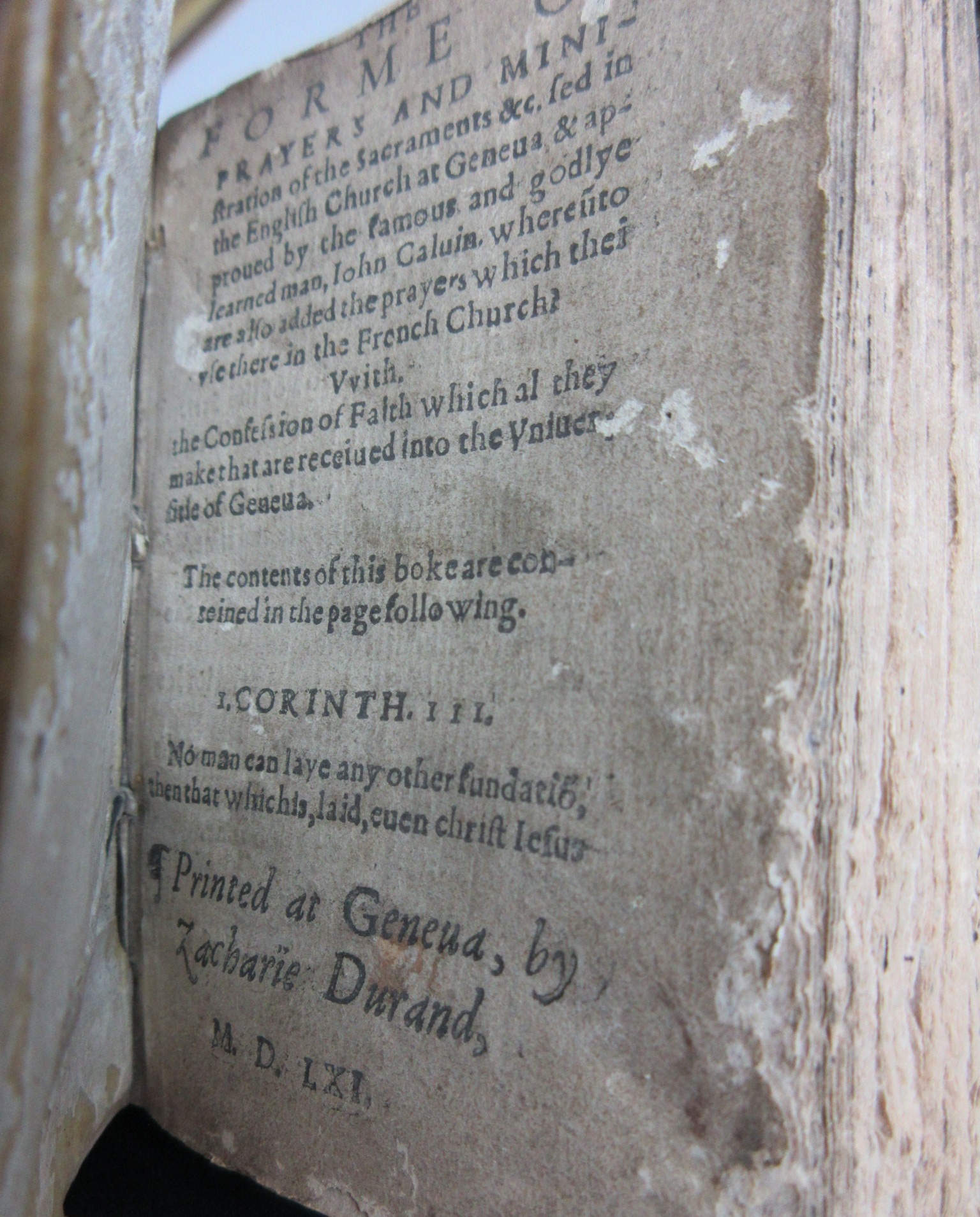

Besloten hof, het innigh ghebedt betuynt met de doornen-haghe der verstervinghe (Enclosed Garden, the Inner Prayer Bordered with the Thorny Hedge of Mortification) (Antwerp: Arnout van Brakel, 1665) is associated with two female communities. It is dedicated to Maria van Praet (d. 1668), who at the time of publication was “hooftmeestesse” (“grand mistress”) of the beguinage of Antwerp. Later, the book ended up in a women’s convent (possibly of Discalced Carmelite nuns) in Willebroek, a little town south of Antwerp. The ownership inscriptions at the fly leaf at the front show how the book was passed from person to person within the convent, presumably after the previous owner died. Under Sister Theresia Helman’s name the inscription “Requiescat in Pace” was added, and Sister Joanna van Luijtelaer’s name was followed by the abbreviation “R.I.P.”. Presumably Sister Anna t’Kint, who wrote her name at the top of the page, was the book’s new owner.

Some books were more likely owned by secular women. Den catechismus van S.te Theresia, for instance, is said to have been in the possession of “Joanna Chaterina Roovers woonende in de Copper straet inden wieten engel” (“Joanna Chaterina Roovers living in the Copperstraet in the White Angel”; fly leaf at the front). Unfortunately, it is not clear where the Copperstraet was. The third volume of Het leven vande weerdighe moeder Maria a s.ta Teresia, (alias) Petyt can be located more precisely. It was owned by Joanna Francisca van der Eijnde who lived “op den tribunael tot Mechelen” (“at the tribunal in Mechelen”; fly leaf at the front). She probably belonged to a family of painters whose members lived and worked as porters in that same tribunal (the court of justice). Remarkably, Arnold Frans Van den Eynde (1793–1885), a possible family member of Joanna Francisca, painted the Carmelite convent in Mechelen where Maria Petyt lived as an anchorite in the last phase of her life.

Towards an Inclusive Literary History

Our exploratory research in the library of the Ruusbroec Institute shows the importance of research into handwritten inscriptions in printed books. It shows that there is still a world to discover when it comes to the relationship between women and (religious) book culture in the early modern period. Both religious and secular women participated in the production, reception, and circulation of seventeenth-century printed books in many different ways. In several books, women’s spiritual ideas were passed on by men who wanted to make their voices heard. Books were dedicated to women or put out to print by them. Many copies reached female audiences. In some cases, we find that books were passed down from woman to woman for generations.

Our work also underlines again the importance of enhancing access to heritage collections and making material evidence in individual copies available. A systematic exploration of early printed book collections will bring visibility to large numbers of women. Provenance data in early printed books can teach us which women read and wrote or were otherwise involved in the book culture of their time. Such data can also be used to discover what women read, for what reason, and in what context. It is this type of research into women’s books that will help us eventually to construct an inclusive history of early modern Dutch literature.

Note: This blogpost was developed within the module “Women and early modern literature” of the BA-course “Dutch Studies in Practice” (“Neerlandistiek in de praktijk”) of the Language and Literature program of the University of Antwerp. The research was carried out by Noah Claassen, Ynys Convents, Kevin De Laet, Ellen Gommers, Ingeborg de Heer, Eline Heyvaert, Joran Jacobs, Anouck Kuypers, Sebastiaan Peeters, Jade Simoens, Emma Ten Doesschate, Cynthia Thielen, Lotte Van Grimberge, and Jens Van Reet, under the supervision of Tine De Koninck and Patricia Stoop. The text was written by Ynys Convents, Ellen Gommers, Sebastiaan Peeters, Emma Ten Doesschate, and Patricia Stoop.

Source: Books held by the Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, Antwerp. All images reproduced with permission.

Printed books studied

Besloten hof, het innigh ghebedt betuynt met de doornen-hage der verstervinghe (Antwerp: Arnout van Brakel, 1665) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, RG 3079 D 14).

[Daniël Huysmans], Kort begryp des levens ende der deughden vande weerdighe Joanna van Randenraedt (Antwerp: Augustinus Graet, 1690) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, 3054 H 3 gamma).

[Daniël Huysmans], Leven ende deughden vande weerdighe Agnes van Heilsbagh (Antwerp: Michiel Knobbaert, 1691) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, 4050 A 12).

Den catechismus van S.te Theresia (Antwerp: Hieronymus Verdussen V, [1687]) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, 3018 I 23bis).

Francisco Ribera, La vida de la madre Teresa de Iesus, fundadora de las Descalças, y Descalços Carmelitas (Salamanca: Pedro Lasso, 1590).

Francisco Ribera, La vie de la mere Terese de Jesus, Fondatrice des Carmes dechaussez (Antwerp: Gaspar Bellerus, 1607).

Francisco Ribera, Het leven der H. Moeder Terese van Iesus fundaterse vande barvoetsche carmeliten ende carmeliterssen (Antwerp: Joachim Trognesius, 1620) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, 3053 C 20 gamma).

Michael a Sancto Augustino, Derde deel van het leven vande weerdighe moeder Maria a S.ta Teresia, (alias) Petyt, Vanden derden Reghel vande Orden der Broederen van Onse L. Vrouwe des berghs Carmeli (Ghent: heirs of Jan vanden Kerchove, 1683) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, 3017 C 1 2/1).

Theresa van Ávila, Bruydegoms vrede-kus oft Bemerckinghen vande liefde Godts (Antwerp: Weduwe van Jan Cnobbaert, 1647) (Antwerp, Library of the Ruusbroec Institute, RG 3018 C 18, 1e ex).