Michael Durrant (IES, University of London)

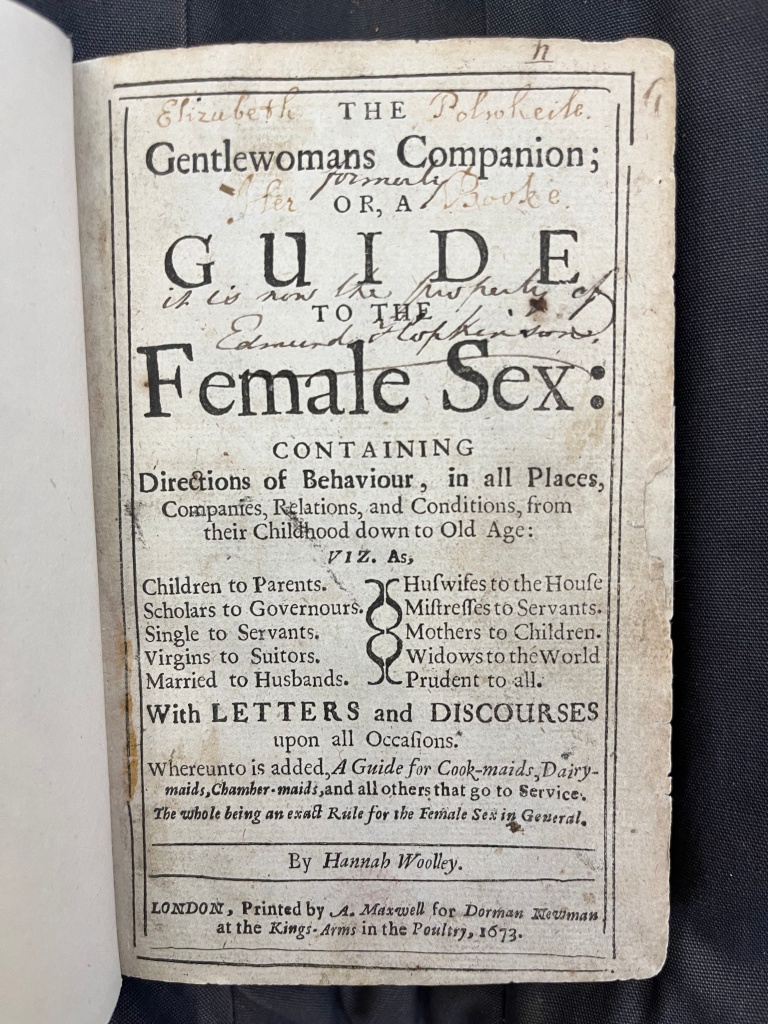

The title page of the 1673 self-help manual, The Gentlewomans Companion; or, A Guide to the Female Sex (ESTC, R204109), discreetly tucks “By Hannah Woolley” at the foot of the text’s long title, sandwiching “Woolley” between two rules and just above the imprint, where we find another female agent being marked out as a key player in this text’s making: “LONDON, Printed by A[nne] Maxwell [fl. 1660-1680] for Dorman Newman at the Kings-Arms in the Poultry, 1673.”

As Martine van Elk has written elsewhere on this blog, Anne Maxwell’s involvement as the Companion’s printer seems fairly well assured, but Hannah Woolley’s involvement as the Companion’s author is rather less clear cut. For sure, Woolley was a likely candidate to be the author of a text that, to quote from the title page again, purports to contain “Directions of [female] Behaviour, in all Places, | Companies, Relations, and Conditions, from | their Childhood down to Old Age.” She had made a name for herself as an expert writer of recipes and matters to do with household management, and so there’s scope to imagine that Woolley really did branch out to pen the Companion, in which tips on cooking, cleaning, human hygiene and health jostle alongside prescriptions on proper female speech, conversation, gait and posture, and guidelines for the writing of letters. But really The Gentlewomans Companion seems to have been spurious, an attempt by its publisher, Newman, working alongside its printer, Maxwell, to cash in on the Woolley brand

Whilst it has been suggested that the Companion may have been based on an authentic Woolley manuscript,[1] Woolley would publicly disown the text soon after its publication in 1673, complaining in a dedicatory poem that accompanied A Supplement to the Queen-like Closet (1674) that her “Name” had been “much abus’d” by the Companion; Woolley had in fact been “far distant” when the Companion was printed; and since her authorial identity (her “Name”) had been appropriated without her consent, Woolley concludes by asserting “that Book to own I think not fit.”

The whole issue of appropriation—and with this, the idea of where early modern books come from—is addressed in the Companion’s epistle, “To all Young Ladies, Gentlewomen, and all Maidens whatever,” which is allegedly Woolley-authored. There, “Woolley” tells us that, given the commercial success of her other print products (“the first called, The Ladies Directory; the other, The Cooks Guide”), she had been encouraged by both her “Book-seller” and her “worthy Friends” (sig. A3r) to write a more fulsome “Companion and Guide to the Female Sex” (sig. A3v). Over the course of seven years, “Woolley” read and researched her way through several contemporary manuals on female instruction, including “that Excellent Book, The Queens Closet; May’s Cookery; The Ladies Companion,” her own “Directory and Guide,” as well as fashionable books “lately writ in the French and Italian Languages” (sig. A4r-v). “Woolley” then settles on imagery associated with the painting of portraits to account for the way in which she actively folded words and ideas from these books into her own writing:

I hope the Reader will not think it much, that as the famous Lymner when he drew the Picture of an exact Beauty, made use of an Eye from one, of a Mouth from another, and so cull’d what was rare in all others, that he might present them all in one entire piece of Workmanship and Frame: So I, when I was to write of Physick and Chyrurgery, have consulted all Books I could meet with in that kind, to compleat my own Experiences (sig. A4v–A5r).

Quoting the same passage, Leah Orr suggests that “[s]uch “culling” is very generally practiced [in the period] but rarely stated so forthrightly.”[2] Given Woolley’s own complaint that the Companion had actually “abus’d” (or we might say “cull’d) her “Name” and therefore her brand identity, there appears to be something cheekily self-referential at work here. Indeed, the “Lymner” imagery—and with this, the idea of an individual’s portrait being made of bits and pieces drawn from the bodies of other subjects—seems particularly pointed given the fact that the Companion was published alongside a paratextual portrait, which was supposed to be in the likeness of Woolley herself, but that was really a retouched image of someone else.

Turning now to the British Library’s (BL) copy of The Gentlewomans Companion (C.194.a.1455), we can see that the issues of appropriation I’ve been discussing find expression in evidence related to book use and competing claims to book ownership.

This copy lacks the suspect Woolley portrait, although on its title page we do find a seventeenth-century inscription, written in brownish ink, which designates female ownership: “Elizabeth Polwheile her booke.”

Writing for the BL’s “Untold Lives” blog, Beth Cortese suggests that this “Elizabeth Polwheile” is likely the Restoration playwright, Elizabeth Polwhele (c. 1651–1691), who was the author of at least two unpublished plays, The Faythfull Virgins (c. 1670) and The Frolicks, or The Lawyer Cheated (c. 1671). It’s an exciting possibility, because as Cortese points out, it would offer us a little glimpse into the library of a woman about whom we still know little, and her ownership of “Woolley’s” Gentlewomans Companion might suggest that this text was being used not only for educational purposes but perhaps also as one of Polwhele’s “literary influences”.

This scenario—that Polwhele read the BL’s copy of the Companion for the bits that could be “cull’d” to form the basis of her own writing—might explain the presence of two hand-drawn crosses (+) that are positioned in the margins of this book. Written in what appears to be the same brownish ink used to write the “Elizabeth Polwheile her booke” inscription, these marginal notations materialise in the concluding section of the book, where “Woolley” offers a suite of imaginary/stock “Letters upon all Occasions” (sig. Q3v–S3v). The first cross appears in the left-hand margin of “The Answer of an ingenious Lady” (sig. Q8v). This letter serves as a reply to the preceding “Letter from one Lady to another, condemning Artificial-beauty” (sig. Q7r–Q8r), and it finds the “ingenious Lady” arguing for a woman’s right to wear cosmetics, and she fights back at prevailing stereotypes that linked the “Art in the imbellishing” with female “sin”, “pride” and “vanity” (sig. Q8v). The second cross appears in the right-hand margin of “A Lady to her Daughter, perswading her from wearing Spots and Black-patches in her face” (sig. R2r), in which another “Lady” adopts an entirely antithetical line, neurotically linking cosmetics and female fashions with libertine excess and therefore with “the vices of this present age.”

I don’t know for sure whether these two crosses were put there by Polwhele, but if she is responsible for these markings, perhaps it’s evidence of her reaching into “Woolley’s” Companion to mark-up moments that might be usefully appropriated within the contexts of her own dramaturgy—serving, say, as a source for ready-made dialogues between female characters who could represent competing forms of femininity.

So, a book that seems to have appropriated the Woolley brand, and a book that, at the same time, draws attention to rather than obscures its own literary appropriations and borrowings, may have become a site of creative appropriation for at least one female Restoration playwright. But then returning to the title page of the BL’s copy of The Gentlewomans Companion, we find another, later hand reaching into the text to mark out another identity, another form of ownership, and with this, another layer of appropriation.

Just under the “Elizabeth Polwheile her booke” statement, a male hand has inserted the word “formerly”; just below that, the same hand then adds that Polwhele’s book “is now the property of Edmund Hopkinson”—that is, Edmund Hopkinson (1787–1869) of Edgeworth Manor House near Cirencester, who was the High Sheriff in Gloucestershire. An avid collector of antiquities—including, by all accounts, an Egyptian mummy, which he unwrapped during a dinner party before donating to the Gloucester Museum in the 1850s—Hopkinson steps in to appropriate the title page of The Gentlewomans Companion as a space to enact his own masculinist (self-)possession. Nudging Polwhele to the side, the book seems to become Hopkinson’s “property,” but in the case of The Gentlewomans Companion, where issues of possession and attribution and appropriation seem to be constantly shifting and recalibrating, such an assertion is really more complex than it might first appear.

Source: copy held at the British Library, shelf mark C.194.a.1455. Photos by Michael Durrant, reproduced with permission.

[1] See Margaret J.M. Ezell, “Cooking the Books; or, The Three Faces of Hannah Woolley,” in Reading and Writing Recipe Books, 1550–1800, ed. by Michelle DiMeo and Sara Pennell (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013), pp. 159–78.

[2] Leah Orr, Publishing the Woman Writer in England, 1670-1750 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023), p. 61.