By Michele D. Pflug

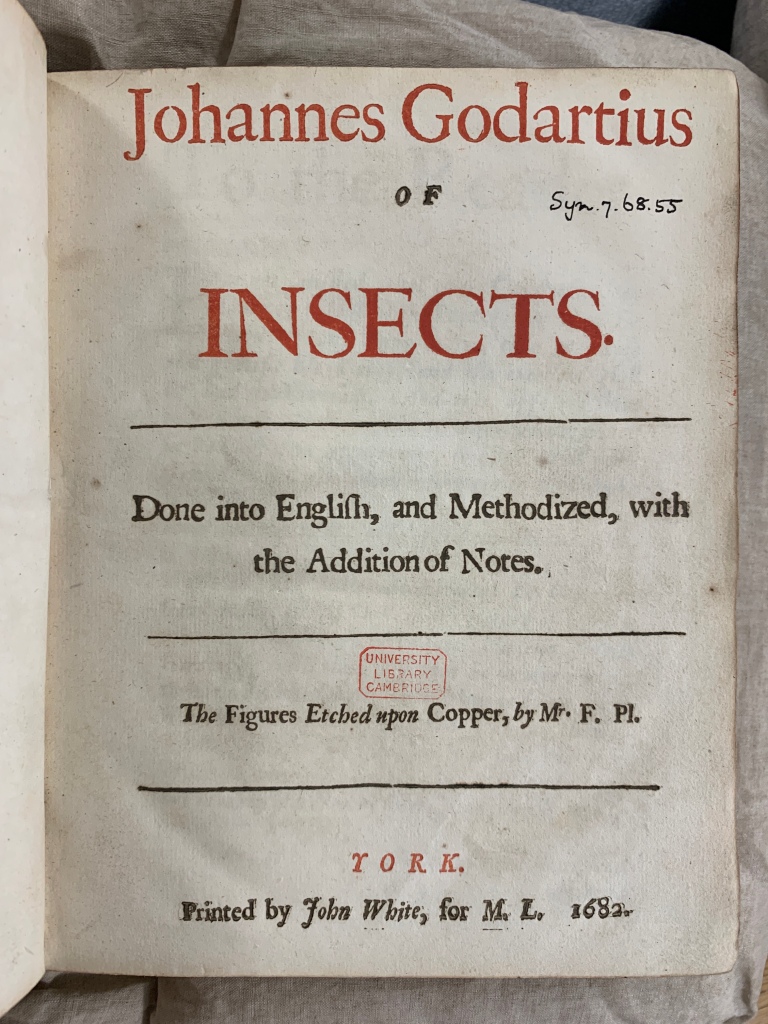

On December 28, 1702, the English gentlewoman Eleanor Glanville crafted a list of observations on insects. She referenced figures from a printed book to aid her descriptions: Johannes Goedaert’s Of Insects: done into English, and methodized, with the addition of notes, translated by Martin Lister (1682) (figure 1). Glanville was quite critical of the etchings, noting that the plates were “not wel figured” (British Library, Sloane MS 3324, f. 20).

Eleanor Glanville clearly owned a copy of Lister’s English translation. Her observations demonstrate how printed books could shape scientific practice and communication in real time. Yet, her very ownership of this book, a rare item with only 150 copies ever printed, raises questions about how this text circulated and what kinds of audiences ultimately had access to it.

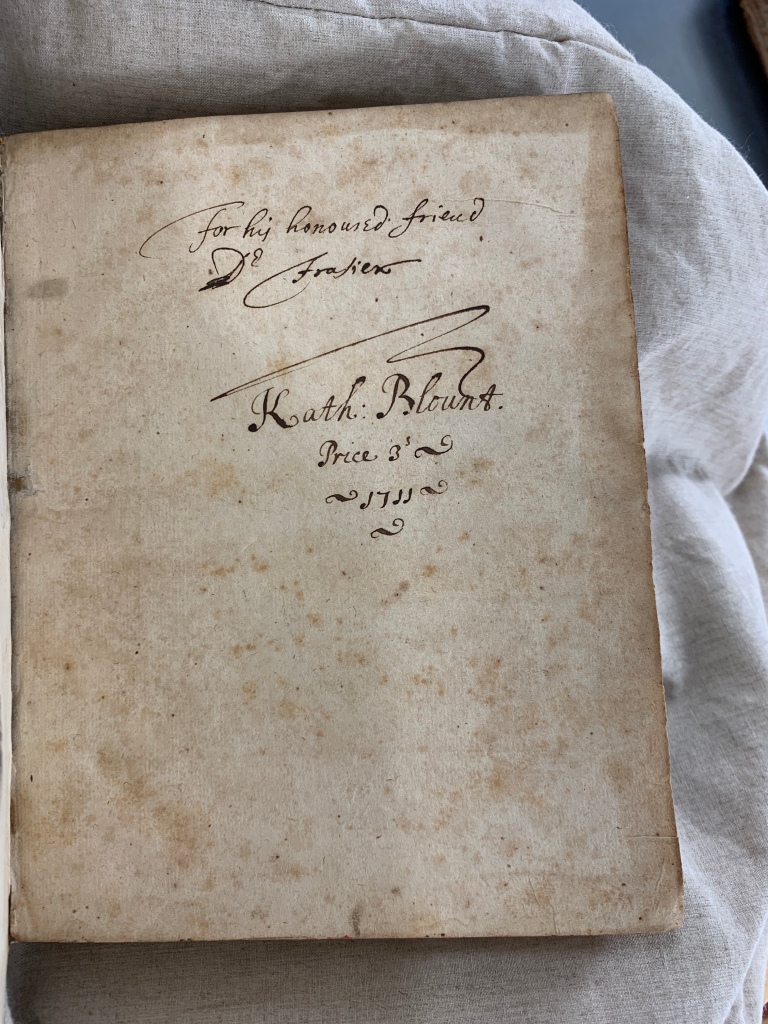

While I have yet to locate Glanville’s copy—that is, if it even still exists—I have had some unexpected results while searching for it. When I ordered the text from Cambridge University Library (Syn.7.68.55), I was surprised to find an ownership inscription from Katherine Blount on the front flyleaf (figure 2). Underneath Blount’s signature, she recorded that she purchased the text in 1711 for 3 shillings. Written above, in a different, likely older hand, is the inscription “to his honoured friend Dr Frasier.”

I had never heard of Blount, but of course, finding a woman’s name inscribed in a scientific text piqued my interest. A quick Google search brought me to this blog, where several researchers have already compiled evidence on Blount’s book ownership. Sarah Lindenbaum first brought Blount to scholarly attention in 2020. Sophie Floate, William Poole, Mary-Ann O’Donnell, Victoria Burke, Martine van Elk, and Joseph Black have all added more titles to her library.

Most titles are literary, but the number of scientific texts known to be owned by Blount is steadily increasing. These titles include Francis Willughby’s The Ornithology (1678), acquired by Blount in 1730, Hales’s Vegetable Staticks, gifted to Blount by the author in 1727, and Francis Bacon’s Sylva Sylvarum (1685), bought by Blount in 1699. As Martine van Elk suggested in her recent post, these works suggest that Blount may have had an interest in natural history.

The addition of Goedaert’s Of Insects to Blount’s library adds weight to this theory. Furthermore, that Blount purchased (as opposed to being gifted) this copy demonstrates an active interest in natural history. Why might Blount have bought this work on insects?

The English Translation of Of Insects

The Dutch artist and naturalist Johannes Goedaert first published his Metamorphosis naturalis in the 1660s. This text would become a landmark in the history of entomology for its detailed descriptions of insect life cycles. In 1682, the English naturalist Martin Lister put out the earliest English translation of the text. Lister explained in his address to the reader that these copies were “intended only for the curious.”

Who belonged to this society of the curious? In 1682, most scientific texts were still printed in Latin. By printing in the vernacular, Lister may have intended to reach a wider audience. Intentional or not, the English translation opened the door for educated, although non-Latinate people, including women, to consult his work.

Katherine Blount’s Copy of Of Insects

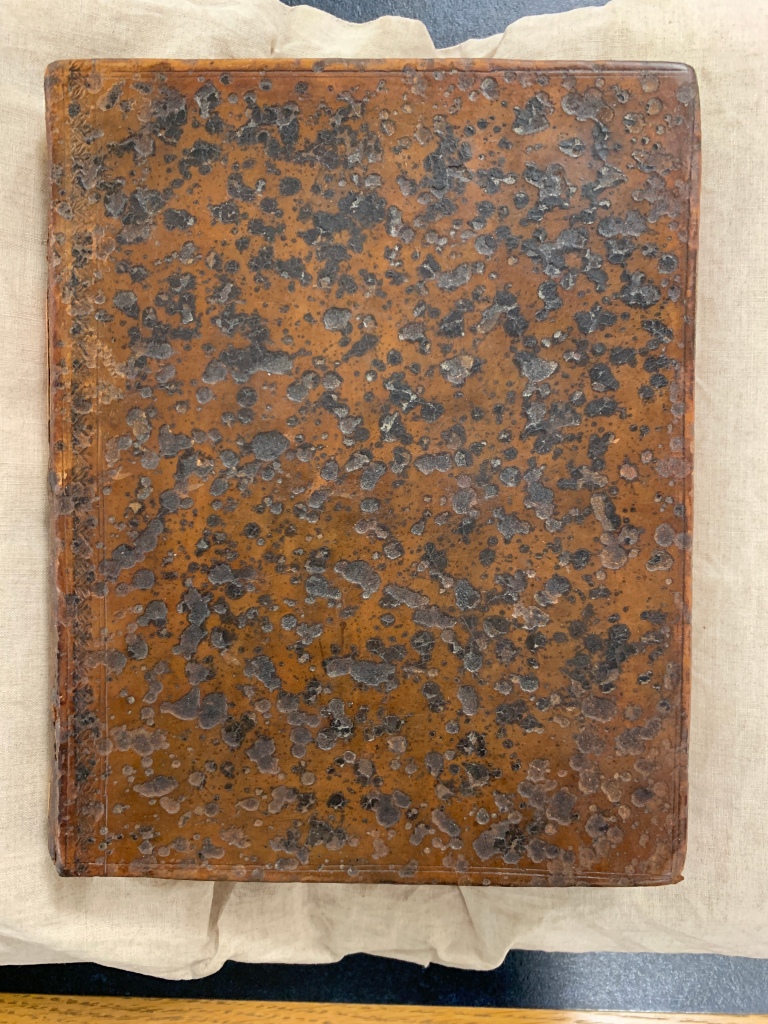

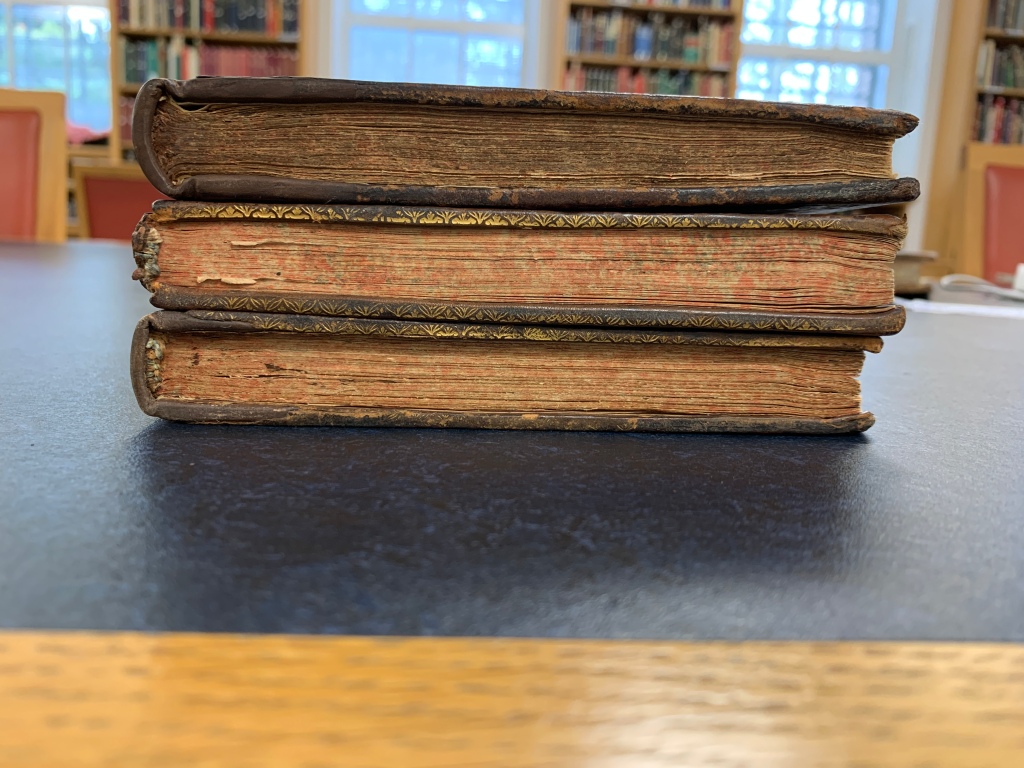

In many ways, Katherine Blount’s copy of Of Insects closely resembles the other fifteen copies I have examined so far. It is a slim quarto volume numbering 140 pages with fourteen fold-out etchings. Despite having wildly different provenances, most copies (including Blount’s) have nearly identical bindings: mottled calf boards with double fillets, the edges gilt-rolled with the same foliated design (figure 3 and 4). Most of the spines have been replaced. The striking similarities between the bindings of multiple copies, held at different institutions, suggests that purchasers had the option to buy the volume as a pre-bound item.

Unfortunately, Blount’s copy does not have any annotations. We don’t know from whom or how she came to purchase it. The inscription above hers, “for his honoured friend Dr Frasier,” suggests a previous owner, although I have not been able to definitively identify Dr. Frasier. Early Modern Letters Online has an entry for a James Frasier, an artist and friend of Martin Lister, John Ray, and Francis Willughby. I’ve also come across a Thomas Frazier who corresponded with John Woodward, a naturalist contemporaneous with Lister, although it is unclear if Thomas was a doctor.

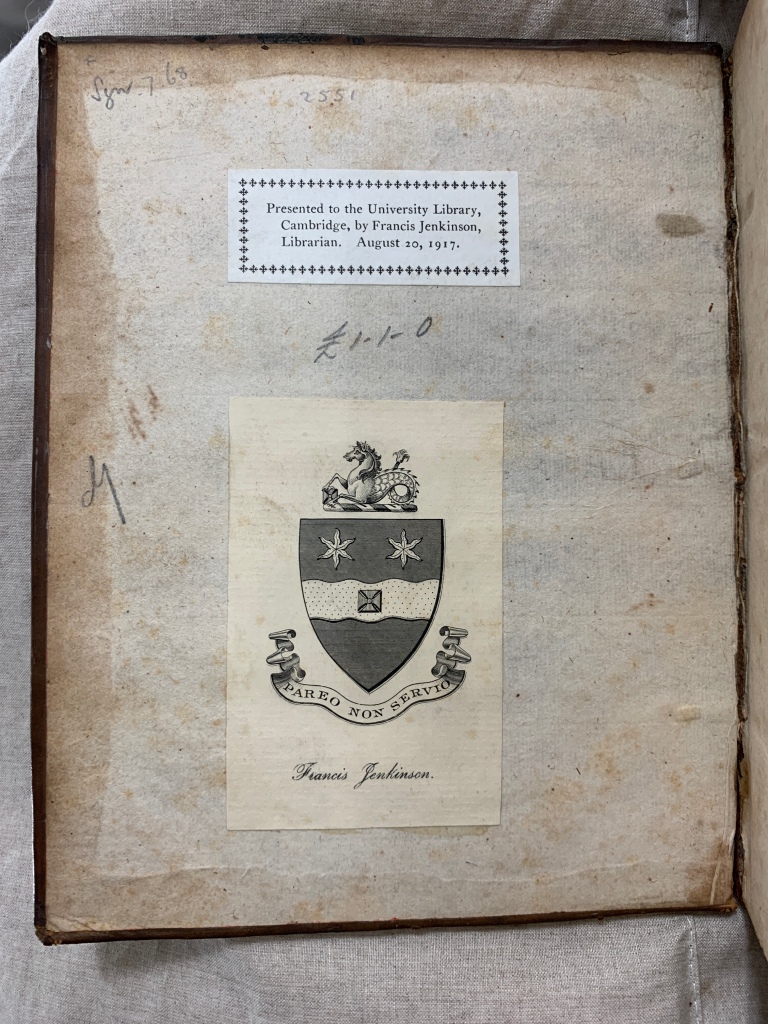

Additional evidence on the front pastedown informs us of the book’s later provenance. It features the bookplate of Francis Jenkinson, the Cambridge University Librarian (essentially the head librarian) from 1889 to 1923 (figure 5). He trained as a classicist but held a wide variety of academic and personal interests, including a zeal for entomology. Martin Lister’s translation of Of Insects would have combined his passion for antiquarian books and insects. He donated this copy to the Cambridge University Library on August 20, 1917.

Women and the Culture of Collecting

Both Eleanor Glanville and Katherine Blount owned this scientific text. We know that Glanville and other naturalists used it as a model to write observations and organize their collections. Might Katherine Blount have done the same? The best source for biographical information about Blount, A History of Tyttenhanger (1895), first located by Sarah Lindenbaum, contains a clue, albeit an uncertain one. The author, Lady Jane Van Koughnet, writes of Blount that “she had a large collection of all sorts of curiosities” (66). Van Koughnet then lists a wide range of man-made curiosities that still survived at Tyttenhanger: a jewel box, ornamental arrows, a Chinese cabinet holding coins, an ivory crucifix, Chinese idols, and other objects.

Katherine Blount would have collected these objects in an age when the boundaries between natural and artificial curiosities were porous. A single collector might as easily hold ancient coins and dried plants, antiquarian manuscripts and beetles, or elephant tusks and paintings in the same collection. These cabinets of curiosities were often heterogeneous, some bordering on encyclopedic.

Given this historical context and Katherine Blount’s predilection for collecting, it is possible that she collected natural curiosities too. Such biological specimens, unlike the durable man-made objects listed in A History of Tyttenhanger, would not have survived the intervening centuries, at least not without an intensive amount of preservation.

Without further evidence, though, the idea of Katherine Blount as a collector of naturalia remains pure speculation. Together, her scientific texts cover birds, butterflies, and plants. These would have been fashionable curiosities for a woman, described as “gifted with a mind full of energy,” to collect (Van Koughnet, 65).

Source

Cambridge University Library, shelfmark Syn.7.68.55. Photographs by Michele D. Pflug, used with permission.

Further reading

H. F. Stewart. Francis Jenkinson, Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, and University Librarian: A Memoir. Cambridge: University Press, 1926.

Van Koughnet, Jane C. E. A History of Tyttenhanger. London : M. Ward, 1895. http://archive.org/details/historyoftyttenh00vank.