By Beth DeBold

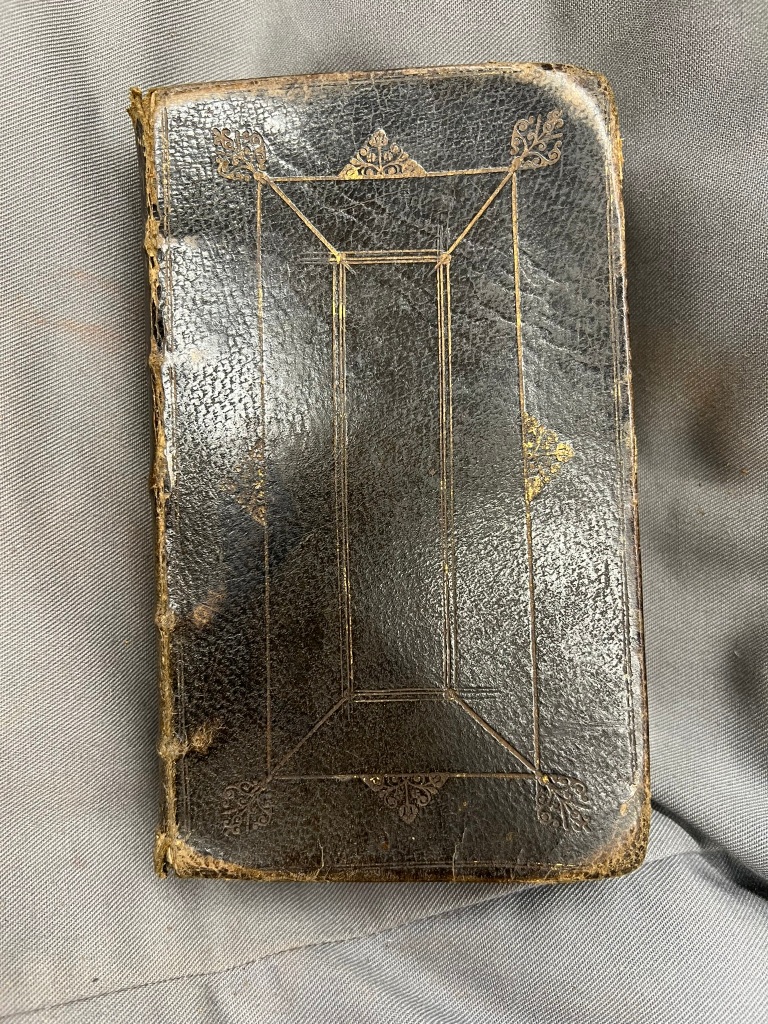

These two devotional texts, bound together in dark brown goatskin with faded gilt ornaments and fore-edges, represent a fairly commonplace survivor of the early eighteenth century. The fact that the book contains, above two decorative title pages, the inscriptions of two women is also not extraordinary. As book historian David Pearson notes, such titles were often bound together by or for sellers in relatively elegant, up-market bindings; likely in anticipation of their use as good gifts for ladies (Pearson, 504).

This book has certainly been well-used: the joints are cracked and rubbed, while the edges of the boards are worn and curled inwards. The gilt has faded away from the tooling on the covers and the edges, and the grubby pink, blue, and white endbands have separated away from the hinges.

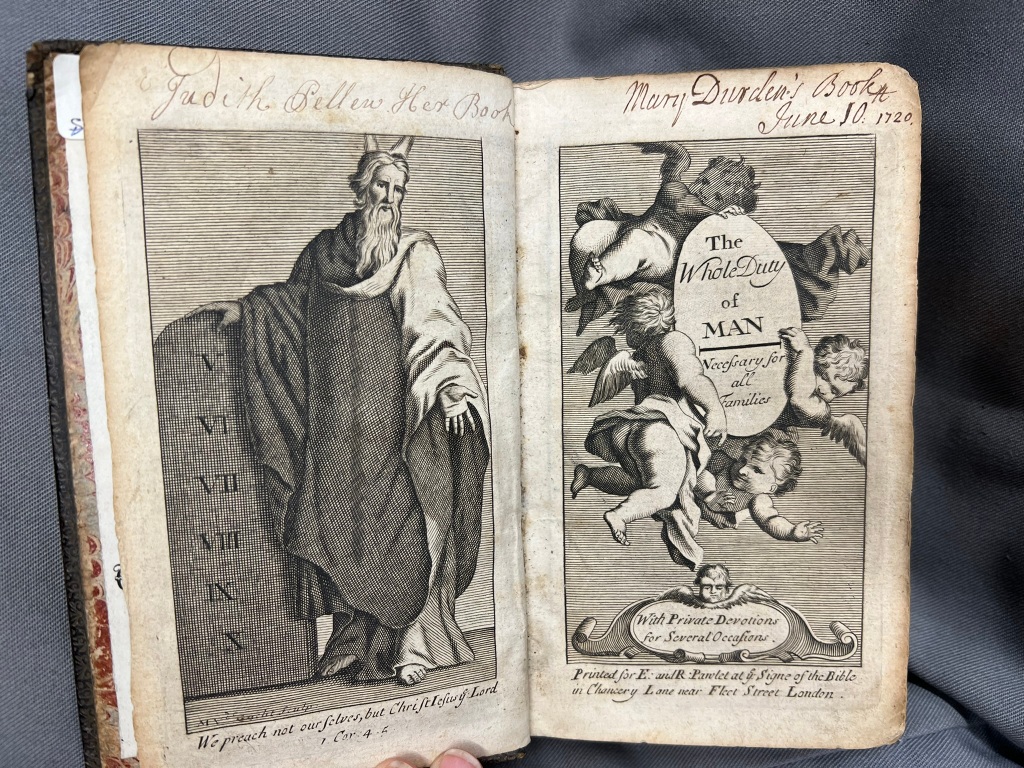

This binding has done its work: inside; the text block is in fair condition. On the leftmost engraved title, above Moses posing gamely with his tablets, one early owner has written “Judith Pellew Her Book” in slightly faded, round letters. Pellew provides us with slightly embellished majescules in this signature and an elegant arch to the miniscule “d” in her first name. The very top of this “d” has been cut off, suggesting that despite its contemporary appearance, the text block has been rebound at least once. On the facing page, above a bevy of mischievous putti who hold a decorative title piece aloft, is a slightly darker, plainer signature: “Mary Durden’s Book June 10 1720.” Mary’s signature is slightly more oval than round; the majescule “D” in her surname is exceptionally dark, as though she has borne down on her pen, or refreshed her quill when it ran out of ink. A small flourish at the end of the word “Book,” really no more than a hash, offsets the general frank plainness of her style.

Vital records turn up few possible candidates, and none who can be positively identified with either name. As with many women whose names remain in old books, this is where the trail goes cold. We may never know who Judith Pellew and Mary Durden were or who they could have been to one another: mother and daughter; sisters; companions or friends; even complete strangers, one of whom had the book re-bound after purchasing it second-hand. Given the way her signature is cut-off, it is likely that Judith’s name is older; but it is still not possible to say with absolute certainty which woman put her name to it first. We are left grasping at the smallest nuances for any ideas about who they might have been and what their lives were like: analyzing how they scrawled their names on facing title pages feels both futile and intimate.

This, as so many other authors have noted here, is the business of researching women’s book ownership. Often left without the obituaries, public careers, and government documents that so many men left behind, we must be content with two things: the simple persistence of their names on a page and the objects themselves which they once held, read, and absorbed. Frustratingly, neither Judith nor Mary, or any other readers, made notes, underlined words, or wrote their diaries on the endleaves. But there is some small evidence here for how these two readers (or others) may have read this book, expressed in the damage that the human body visits on paper.

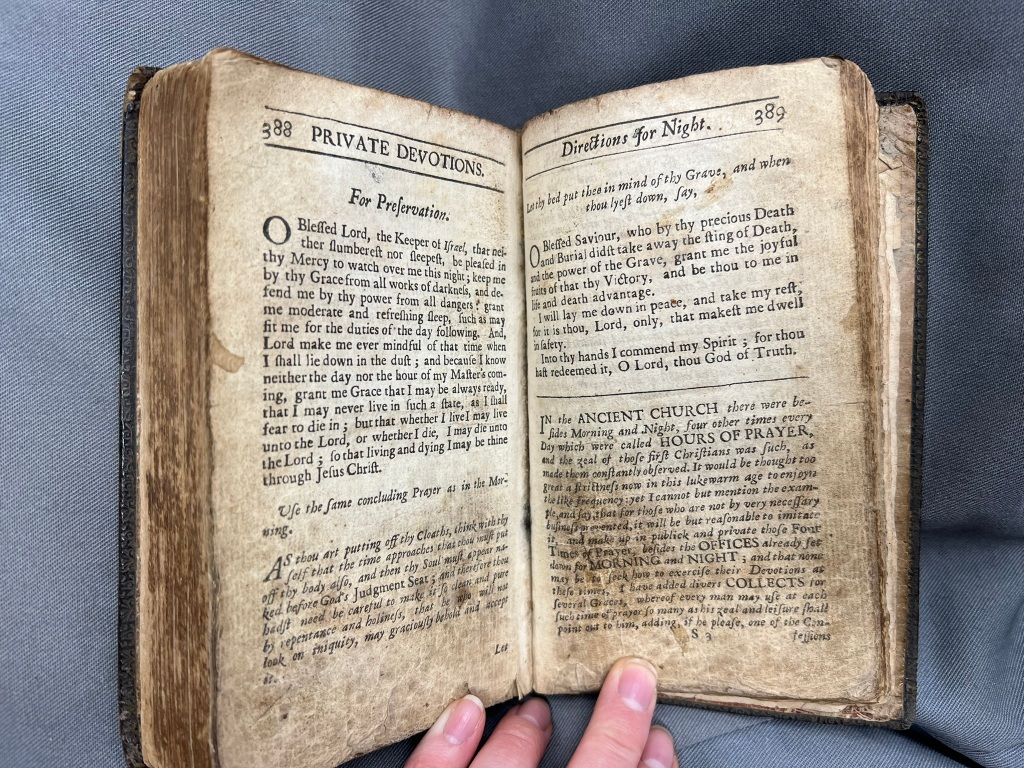

Women are so often objectified and reduced to nothing more than their physical bodies that it feels cheap to focus on the ways that their bodies may have interacted with these texts, but this is the evidence available. As mentioned earlier, the text block overall is in generally good condition; in The Whole Duty of Man, the pages are overall whole, crisp, and without any significant tearing or losses to the edges. The gutters are clean and free of dust and debris. The text block for Private Devotions, however, shows signs of continuous, perhaps meditative, handling. Beginning with the second leaf of the text, page 377, which is headed “Prayers for the Morning,” the lower rightmost corner of each page is soft, dirty, and at different places, even shiny. Small, running tears eat into the text from the margins. This damage is most pronounced through page 385, which is headed “Prayers for Night,” and ending around page 409, which starts a section of excerpts from the Psalms. Along the way, the gutter is filled with detritus: little bits of fluff, hair, crumbs, and other anonymous matter.

It is stating the obvious that this portion of these two copies was the most read, pored over, and continuously revisited. Although it is possible that the second text was pulled from another copy and never in fact belonged to either woman who signed at the beginning, they were printed in the same year for the same person (the mysterious E. Pawlet, who it seems likely was Elizabeth Pawlet (nee Simpson), whose husband Edward died in 1702), and so it is reasonable to presume that this copy of Private Devotions has remained with this copy of The Whole Duty of Man for some time. The interplay between the bodies of the reader(s) and the body of the book tells us what these two women might have found most significant to their daily lives; the wear to the binding shows how often they might have hooked a finger around the endcap to pull it from a shelf, sliding it against other books in their libraries. Perhaps, as with some other reading practices around devotional texts, they might have kissed the pages. What is undeniably true is that it was a book sold by, owned by, and of importance to the women to whom it belonged.

My thanks to Dr Ruth Frendo, Archivist at the Stationers’ Company, for her support and assistance.

Sources

Allestree, Richard. Private Devotions for Several Occasions… MDCCXII [1712]. The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers. No shelf mark assigned.

Allestree, Richard. The Whole Duty of Man. 1712. STC N66291 https://estc.printprobability.org/record/ceae6983fb59f_dashboard_generated_id. The Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers. No shelf mark assigned.

Photos posted with permission.

Further Reading

“Pawlet, Elizabeth.” In The London Book Trades: a biographical and documentary resource. Ed. Michael Turner, 2007. http://lbt.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/mediawiki/index.php/LBT/06645.

Pearson, David. (2020). Bookbinding History and Sacred Cows. The Library. 21. 498-517. 10.1093/library/21.4.498.