Today’s post adds to the small but growing number of books on this site categorized as science and natural history: for additional examples, including two other works by Francis Bacon with female ownership, see the posts here, here, and here.

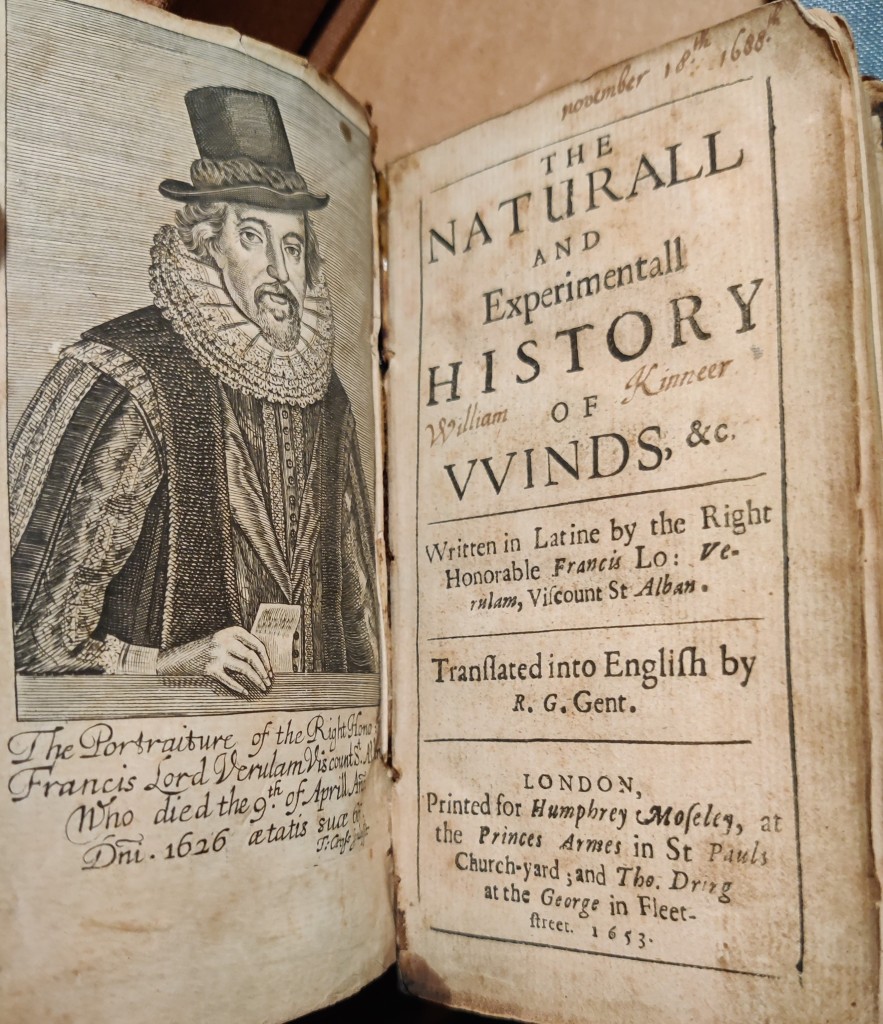

First published in Latin as Historia Ventorum in 1622, Francis Bacon’s Naturall and Experimentall History of Winds served to exemplify his proposed new scientific method of inquiry. The nature and causes of wind had been the subject of scholarly dispute since the classical period, and Bacon offered a usefully comprehensive survey of all facts and theories on the subject available at the time. While he added some new theorizing and presented some interesting information about the utility of a proper understanding of wind, especially in shipping, Bacon’s treatment of the subject is more a simulation of his new model than a data-driven demonstration of his ideal.[1] In recent years, however, the book has started to be cited by literary and other scholars interested in early modern conceptions of wind and in attempts to harness wind for human purposes.[2] This 1653 edition (Wing B305, Gibson 115) is the first publication of the English translation, ascribed to Robert Gentili.

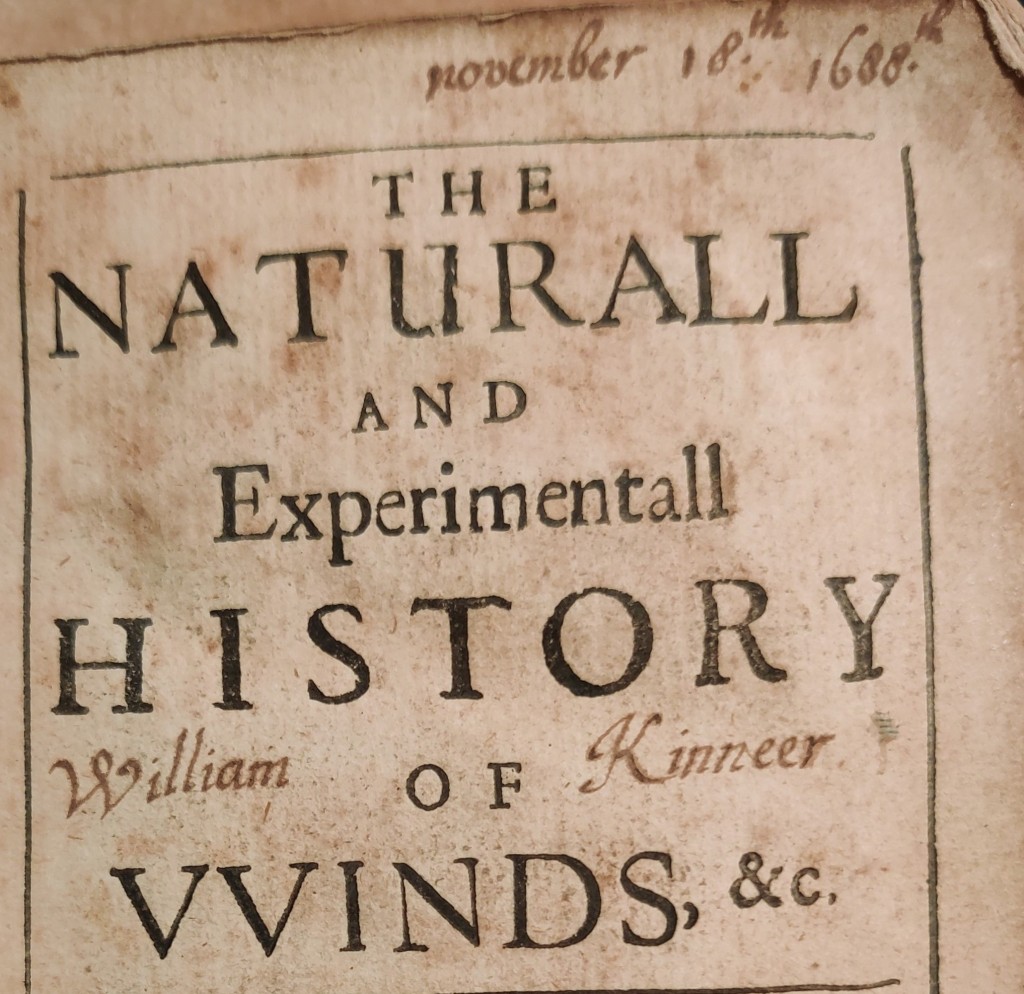

This copy of Bacon’s Naturall and Experimentall History of Winds passed through several hands: it features three early signatures, one of them that of a female owner, and an early Latin inscription in yet another hand. Only one of the signatures is dateable: an unidentified William Kinneer has signed the title-page, adding the date November 18, 1688. Since he is inscribing the book 35 years after its publication, Kinneer is unlikely to have been the book’s first owner. A Benjamin Weston, also unidentified, has signed the verso of a rear flyleaf in a hand that likely post-dates that of Kinneer.

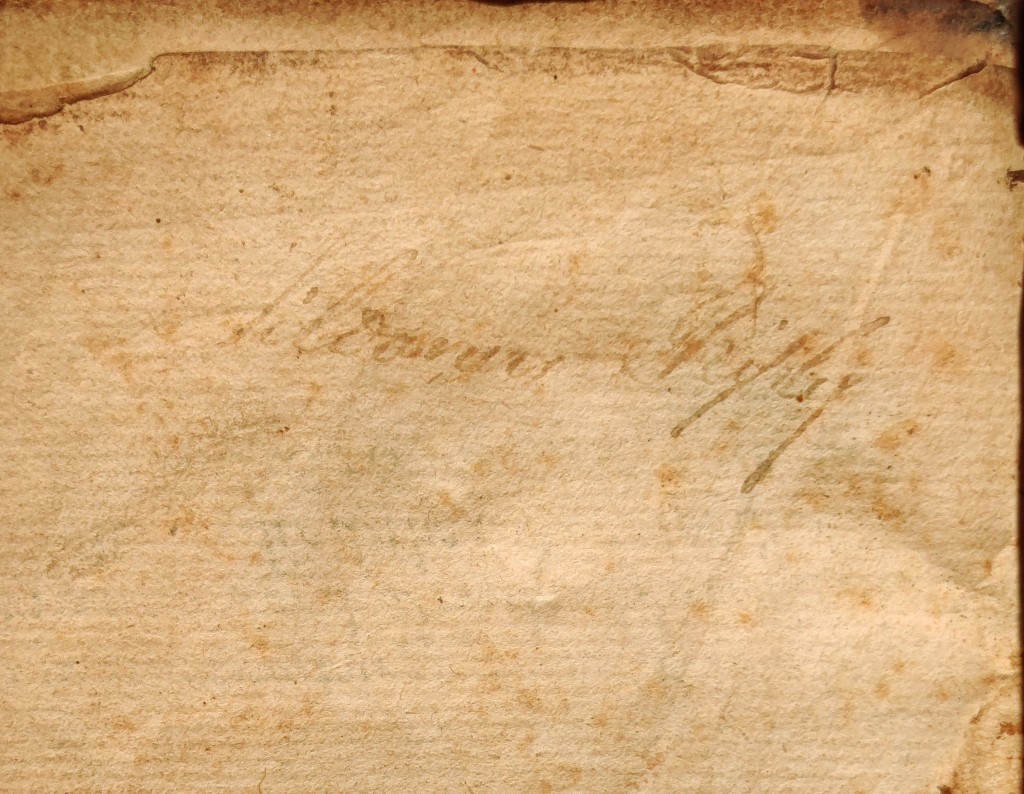

The third (but not necessarily chronologically latest) signature is the one of interest to EMFBO readers: one Lilleanne (possibly “Lilieanne”) Hiply has signed the recto of the frontispiece. The signature has faded, probably because the book has lost both pastedowns and so the recto of the frontispiece and the verso of the rear flyleaf both face the rough paper boards. But when sufficiently enlarged the name is mostly clear (the loops of the initial “L” are visible under magnification) .[3] The name Lillian (spelled in a variety of ways) was not one of the more common ones in the period, but it does start to appear in England in the sixteenth century and the genealogical site ancestry.com offers many seventeenth-century examples. This Lilleanne Hiply remains unidentified: many variations of “Hiply” existed in the period (Hippley, Hibley, Hibly, Hipsley, Hippesley, Hippisley, etc.), making identification a challenge. The signature on its own is difficult to date: it could pre-date Kinneer (1688), but could also follow him. The unusual placement of her signature makes more sense if another signer had already laid claim to the title-page.

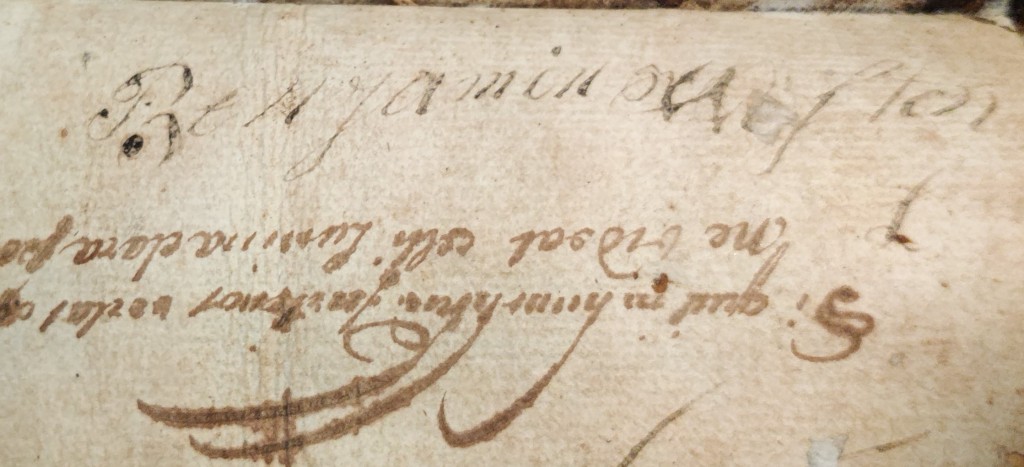

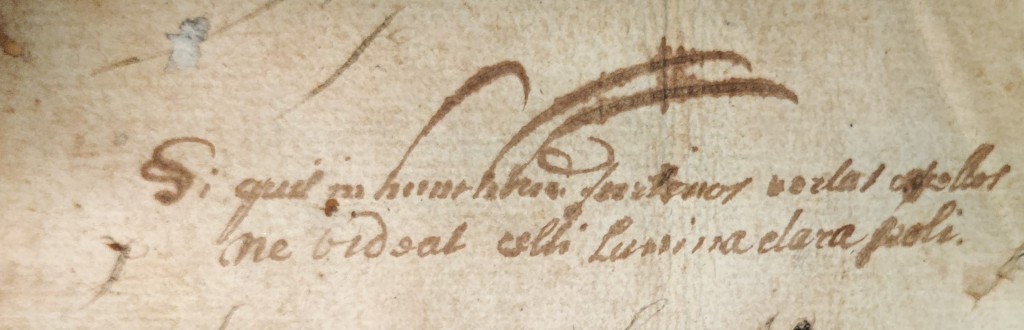

A Latin inscription in a different hand from any of the three signatures appears on the recto of the rear flyleaf: “Si quis in hunc libru[m] furtiuos vertat ocellos / ne videat celli [=coeli] Lumina clara poli.” The Latin is difficult, but the gist is that the lines serve as an imprecation: anybody who neglects or destroys this book will either deserve not to go to Heaven or will/should lose out on scientific knowledge of the heavens.[4] The Latin plays on the subject of Bacon’s book: to neglect knowledge of the winds is to show yourself unworthy of the heavens/Heaven.

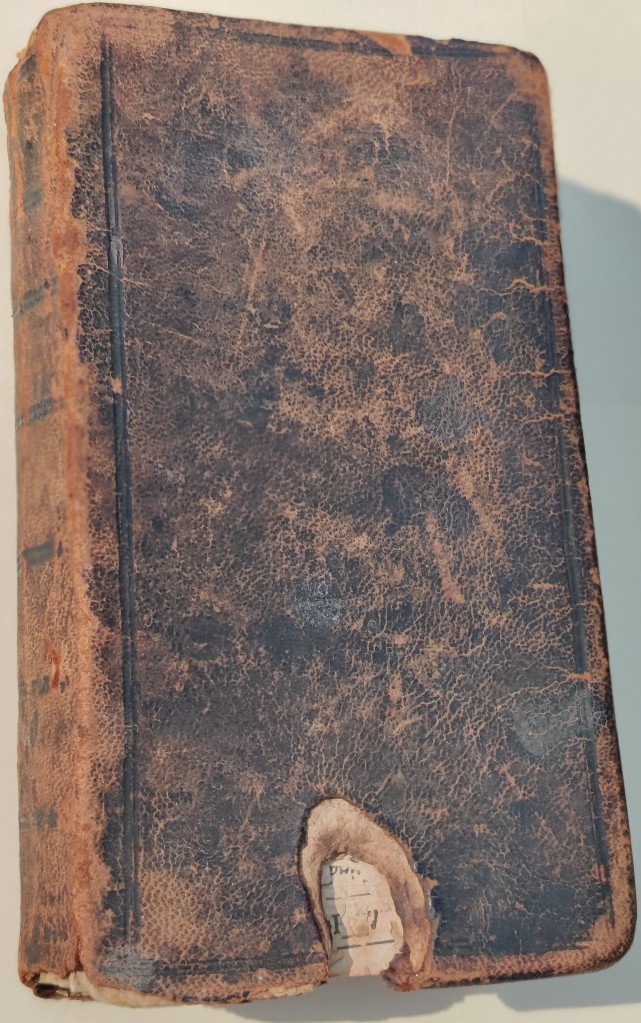

The book retains its original binding, a minimally decorated smooth-spined sheepskin, the kind of binding usually reserved for small-format books (this one is a duodecimo) published to serve the lower to mid-range end of the market. One set of readers has refused to be deterred by the Latin imprecation: the mice who have chewed their way neatly into the lower board.

Source: Francis Bacon, The Naturall and Experimentall History of Winds (1653). Book in private ownership. All images reproduced with permission.

[1] See the introduction to Historia Ventorum in the new edition of the text in the Oxford Francis Bacon, XII: The Instauratio magna Part III, ed. Graham Rees with Maria Wakely (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007), xxxviii-xlvi.

[2] See e.g. Angus Vine, “Francis Bacon and the Mastery of the Winds,” in The Experience of Disaster in Early Modern English Literature, ed. Sophie Chiari (New York: Routledge, 2022), ch. 6; Craig Martin, “Francis Bacon, José de Acosta, and Traditions of Natural Histories of Winds,” Annals of Science 77:4 (2020), 445-68.

[3] I would like to thank Vicki Burke and Tara Lyons for helping me scrutinize this signature.

[4] I am grateful to Stephen Harris, Jacob Ridley, and Tad Boehmer, who all offered expert advice on both the transcription and translation of this passage.